It's been fifty years since twenty-six children perished at the hand of a single man. The sinisterly surnamed Edward Gorey, though, wasn't a notorious mass murderer but rather an esteemed writer/ illustrator whose 1963 masterwork The Gashlycrumb Tinies takes the subject of juvenile demise from A to Z. Gorey's depictions of death encompass the accidental (a tumble down a staircase) and the deliberate (strangulation by thug), the mundane (choking on a peach), and the bizarre (being devoured by mice). Some of the drawings show the youngsters facing imminent mishap, while others pose victims in postmortem ignominy.

The common denominator is dark humor: Gorey's titular Tinies jointly evoke the Victorian (in both name and dress), yet any notion of the prim and proper is ironically undercut within the context of a grim primer.

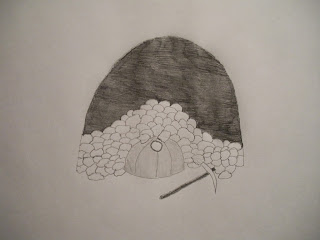

The Jack-O'-Lantern Abecedarium commemorates the golden anniversary of The Gashlycrumb Tinies in orange and black fashion, turning to popular late-October ritual. Pumpkin carving--Halloween's quintessential act of creative destruction--offers terrific opportunity for both self-expression and (if one's not careful) self-infliction. The following "alphabet book" might not be as rife with fatality as its precursor, but it does strive for the same macabre and mischievous sensibility. My goal has been to honor the spirit of the holiday season while paying homage to the ultimately inimitable Mr. Gorey.

The Jack-O'-Lantern Abecedarium commemorates the golden anniversary of The Gashlycrumb Tinies in orange and black fashion, turning to popular late-October ritual. Pumpkin carving--Halloween's quintessential act of creative destruction--offers terrific opportunity for both self-expression and (if one's not careful) self-infliction. The following "alphabet book" might not be as rife with fatality as its precursor, but it does strive for the same macabre and mischievous sensibility. My goal has been to honor the spirit of the holiday season while paying homage to the ultimately inimitable Mr. Gorey.

A is for Andrew,

Who wound up carving his hand, too.

B is for Beverly,

Who decorated oh so cleverly.

C is for Carson,

Who was obsessed with arson.

D is for Dylan,

Who tried to grow penicillin.

E is for Elyse,

Who carved the Mark of the Beast.

F is for Frances,

Who took one too many chances.

G is for Godric,

Who ate candy 'til he got sick.

H is for Herbert,

Who was a bit of a pervert.

I is for Ivor,

Who created an eyesore.

J is for Jordyn,

Who should've brought her gourd in.

K is for Kevin,

Who loved the movie Seven.

L is for Leif,

Who was the neighborhood thief.

M is for Maisie,

Who was just plain lazy.

N is for Nell,

Who never learned how to spell.

O is for Onyx,

Who depicted pumpkin colonics.

P is for Pryce,

Who was committed to vise.

Q is for Quinn,

Who caused a cave-in.

R is for Riley,

Who refused to make hers smiley.

S is for Siri,

Who venerated the eerie.

T is for Tate,

Who had a distinguishing trait.

U is for Ulysses,

Who considered his younger brothers sissies.

V is for Victoria,

Who favored phantasmagoria.

W is for Wilfred,

Who sympathized with the ill-fed.

X is for Xavier,

Who formed a model of misbehavior.

Y is for Yul,

Who was the kind to be cruel.

Z is for Zach,

Who gave his a practice whack.

Now you know your A, B, C's...

Go carve out some more like these.

Special thanks to Lisa S. for providing the illustrations.