Monday, October 31, 2011

"October Ode" (poem)

A third Halloween post to close out Ray Bradbury Month...

October Ode

For these we should be thankful a whole month earlier:

Halloween tree fruitful with frightful pumpkins.

Homecoming of every monster imaginable for a holiday bash.

Black Ferris wheel Methuselah-lizing anyone who rides too long.

Dead man living in the streets, solicited as a scary party prop.

Emissary dog digging up more than bones in the cemetery.

Playing "poison" leading to a grave outcome for some.

Witch-viscera passed gamesomely around a circle in the cellar dark.

Calliope siren song: helluva good time at the Pandemonium Show.

Sundry country scenes, of misted rivers and midnights persistent,

And all the autumn people on parade, manifold as skittering leaves.

So forget Reggie Jackson and his series of Fall Classic homers;

Ray Bradbury will always be the one and only Mr. October.

Labels:

Poetry/Flash Fiction,

Ray Bradbury Month

Jack-o'-Lantern 2011

I thought the only thing unusual about this year's jack-o'-lantern would be that I was using a white pumpkin for the first time, but an unprecedented October snowstorm (@#$&!) here in the Garden State knocked out power and forced me to carve by the light of the battery-operated candelabra fortuitously included amongst my Halloween decorations.

The process wasn't an easy one, but I'm pleased with the end result. I like to think of this werewolf as one of Bradbury's Elliott Family members, howling happily on its way to the Homecoming:

The process wasn't an easy one, but I'm pleased with the end result. I like to think of this werewolf as one of Bradbury's Elliott Family members, howling happily on its way to the Homecoming:

Labels:

Halloween Season,

Ray Bradbury Month

Ray's Vectors: October Dark

[For the previous vector, click here.]

I've saved the most amazing vector for last.

David Herter makes no secret that his 2010 novel October Dark employs Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes as "its ghostly armature." In his Acknowledgments page at book's end, the author also notes his key realization that he "could wield Bradbury's masterwork somewhat like the mirror maze at that novel's heart."

Clocking in at over 500 pages and sporting a fractured narrative structure, October Dark is not easily summarized. It concerns the "secret history of cinema," and the truly (and sometimes darkly) magical basis of movie special fx. A pair of fantasy-film-loving fanboys named Will and Jim (naturally) oppose the schemes of an archvillain (Henri Mordaunt) so menacing, he makes Bradbury's Mr. Dark seem as innocuous as Willy Wonka by comparison. And central to the struggle is a piece of footage from a lost 1957 film entitled Dark Carnival.

Herter's genius here lies in never becoming merely derivative while paying serious homage to Something Wicked. He gifts readers with original riffs on iconic Bradbury scenes, from the attack by a witch in a black balloon to a perilous descent beneath the city streets by Will and Jim. A paean to the childlike sense of wonder, October Dark is itself wonderfully imaginative.

The book is not flawless--the narrative could use some tightening (the plot is slow to unfold, yet builds to a breath-taking climax) and the text is in need of better copy editing (too many typos). But if, like Herter, you grew up adoring Star Wars, Famous Monsters of Filmland, the stop-action marvels of animators like Willis O'Brien and Ray Harryhausen, TV monster-movie hosts, and most of all the dark-fantasy fiction of Ray Bradbury, then you will be nothing short of delighted by October Dark.

***

This wraps up the on-going feature "Ray's Vectors," but I could easily have filled up another month with posts on other novels that have been influenced by Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. There's The Traveling Vampire Show, and Dark Carnival (Serenity Falls, Book 3), and The Night Circus, and Sideshow, and Carnival of Fear, and Full Tilt, and The Last Temptation, and...

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Sunday, October 30, 2011

The Simpsons "Treehouse of Horror": Immediate Reactions

"Treehouse of Horror XXII" just finished airing. Here are some quick thoughts on tonight's episode:

(First of all, it's an added treat when "Treehouse" actually gets to air before Halloween [kudos to Major League Baseball for concluding its season on time and not pre-empting The Simpsons].)

Best quick riff on an iconic scene: an alien Maggie chest-bursting from Bart's astronaut costume.

Best extended riff on an iconic scene: Homer in the car contemplating stealing off with a stash of candy (cf. Marion Crane driving off with her boss's money in Psycho).

Punniest segment title: "The Diving Bell and the Butterball"

Funniest line of dialogue (tie):

--Homer on Halloween decorating: "The one time of year when the squalor of our home works to our advantage."

--Holy-roller Ned Flanders' suggestion to the streetwalker who approaches him: "Spend less time on your back and more time on your knees."

Best moment of the entire episode: the last one, when Abe walks on stage in a dark tutu and asks, "When are we doing the 'Black Swan'?"

This year's episode really seemed to de-emphasize horror, choosing

to spoof movies like 127 Hours and Avatar. Halloween was further displaced by the focus on Christmas in the closing scene. After 22 years, could the "Treehouse of Horror" finally be running out of genre material to skewer? I hope not.

One last thought: as huge as zombies are in pop culture currently, I was surprised the episode didn't make an ironic comment on the craze at some point.

Labels:

A.G.T.V.,

Halloween Season

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#1

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#1."The Emissary" (collected in The October Country)

Never has Ray Bradbury forayed deeper (or more overtly) into October Country than in this 1947 tale. The author's powers of establishing a fall atmosphere are on full display here, as Bradbury writes of "the great season of spices and rare incense," of "leaves like charcoals shaken from a blaze of maple trees." A perennially bedridden boy named Martin can only experience the wider world based on what his Dog fetches back to him, following investigations

"down-cellar, up-attic, in closet or coal-bin...down hills where autumn lay in cereal crispness, where children lay in funeral pyres, in rustling heaps, the leaf-buried but watchful dead." Dog dutifully carries back the signs and scents of the season on its hide: as far as Martin is concerned, "this incredible beast was October!"

The venturesome pet also delivers another embodier of the season: Martin's would-be schoolteacher Miss Haight with her "autumn-colored hair." She forms a close companionship with Martin, before being tragically killed in a car accident. To make matters worse, Dog turns peculiar soon after Miss Haight's death: "In the late last days of October, Dog began to act as if the wind had changed and blew from a strange country." On October 30th, Dog disappears from home, and having now lost his last link to the outside world, Martin sinks into despair:

To Martin, Hallowe'en had been nothing more than one evening when tin horns cried off in the cold autumn stars, children blew like goblin leaves along the flinty walks, flinging their heads, or cabbages, at porches, soap-writing names or similar magic symbols on icy windows. All of it as distant, unfathomable, and nightmarish as a puppet show seen from so many miles away that there is no sound or meaning.But Bradbury's bittersweet narrative takes a decidedly ghoulish turn in its last scene. Dog finally returns home from his mysterious excursion, his previous whereabouts betrayed by his newfound stench--of "the ripe and and awful cemetery earth." Dog apparently has gone digging six feet deep, because at the animal's heels Martin hears the staggering approach of what readers must presume is the undead and unburied Miss Haight. Bradbury brilliantly concludes the story with the repetition of an earlier scene-ending line ("Martin had company") that now takes on chilling new meaning.

Indeed, Martin has (some unwanted) company, but "The Emissary" itself stands alone as Ray Bradbury's finest piece of autumnal short fiction.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Saturday, October 29, 2011

Dark Passages: Something Wicked This Way Comes

Ray Bradbury's poetic powers of description have never been put on better display than when detailing a carny's full-body tattoos. So here's a Dark Passage focusing on Mr. Dark--The Illustrated Man, annotated:

Mr. Dark came carrying his panoply of friends [he is legion], his jewel-case assortment of calligraphical reptiles which lay sunning themselves at mid-night [fitting image for the proprietor of a nocturnal carnival] on his flesh. With him strode the stitch-inked Tyrannosaurus rex [notice how Bradbury personifies the tattoos, creating a sense of ani-mation], which lent to his haunches a machined and ancient wellspring mineral-oil glide. As the thunder lizard strode, all glass-bead pomp, so strode Mr. Dark, armored with vile lightning scribbles of carnivores and sheep blasted by that thunder and arun before storms of juggernaut flesh [a convoluted but evocative metaphor]. It was the pterodactyl kite and scythe [assonance par excellence] which raised his arms almost to fly the marbled vaults. And with the inked and stencilled flashburnt shapes of pistoned or bladed doom came his usual crowd of hangers-on, spectators gripped to each limb, seated on shoulder blades, peering from his jungled chest, hung upside down in microscopic millions in his armpit vaults [the embodiment of Gothic architecture] screaming bat-screams for encounters, ready for the hunt and if need be the kill. Like a black tidal wave upon a bleak shore [similes don't get more ominous than this], a dark tumult infilled with phosphorescent beauties and badly spoiled dreams, Mr. Dark sounded and hissed [a verb choice intimating a Satanic nature] his feet, his legs, his body, his sharp face forward. (158-59)

Work Cited

Bradbury, Ray. Something Wicked This Way Comes. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

Labels:

Dark Passages,

Ray Bradbury Month

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#2

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#2."The Illustrated Man" (collected in Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales)

Bradbury takes us behind the scenes of a traveling carnival in this 1950 tale. Disgusted with his own obesity and desperate to stay employed, tent man William Philippus Phelps opts to become the Tattooed Man. He accordingly visits "a tattoo artist far out in the rolling Wisconsin country," a blind crone (forerunner of the Gypsy Dust-Witch in Something Wicked This Way Comes) who completely inks his skin. She transforms him into an Illustrated Man, a marvel "alive with portraiture. He looked as if he had dropped and been crushed between the steel rollers of a print press, and come out like an incredible rotogravure. He was clothed in a garment of trolls and scarlet dinosaurs."

The old dust-witch informs William that she makes the tattoos "fit each man himself and what is inside him." Also, two would-be tattoos--covered by bandages on his chest and back--have been left incomplete, and will develop from William's sweat and thought. At the Big Unveiling of William's chest tattoo, though, a dire scene is revealed--of William strangling his shrill wife Lisabeth.

"The Illustrated Man" sports a wonderfully weird premise (irremovable, seemingly supernatural tattoos that form "Pictures of the Future"). The story also features a violent climax reminiscent of Tod Browning's controversial carnival-horror film Freaks. Lisabeth (who despises her husband's grotesquerie) drives William to attack her in the very manner depicted by his disturbing chest tattoo. The carnival's freaks are meanwhile drawn by the sound of argument, and William discovers them "waiting in the middle of the night, in the dry grass" outside his trailer. When Lisabeth's murdered body is spotted, the gathered freaks proceed to chase down William and pummel him with the tent stakes they brandish. Carnival justice is mercilessly served.

Amidst this lynching, the freshly-formed tattoo on William's back is uncovered, and the sight of it makes the bloodthirsty mob recoil in horror. The story-concluding description of the tattoo offers a grim image of infinite regress: "It showed a crowd of freaks bending over a dying fat man on a dark and lonely road, looking at a tattoo on his back which illustrated a crowd of freaks bending over a dying fat man on a..."

Interestingly, unlike his novelistic counterpart Mr. Dark, William forms a somewhat sympathetic figure as the Illustrated Man. His tragic fate leaves the reader wondering: was William destined to kill his mean-mouthed wife even if he never got tattooed, or did the eldritch dust-witch mark him with an image that caused his eventual ruination? But one thing is beyond question here: Bradbury's "The Illustrated Man" is a macabre masterpiece.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Friday, October 28, 2011

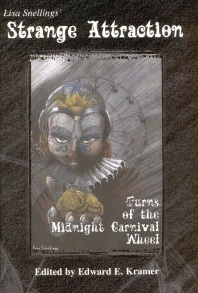

Ray's Vectors: Strange Attraction

[For the previous vector, click here.]

The 24 tales and poems collected in Strange Attraction: Turns of the Midnight Carnival Wheel were inspired by artist Lisa Snellings' kinetic sculpture entitled "Crowded After Hours" (pictured below).

In the foreword to the anthology, editor Edward E. Kramer offers the following description of the macabre Ferris wheel and its unusual occupants: it's "peopled with odd and often haunting individuals, each marked by his or her own history. True to its title, the wheel is quite crowded. Aside from those riding in the wheel's cars are those balanced between its spokes, hanging from its supports and twined in and about its bone-like frame. Each character is at least a step removed from humanity. Some only to a small degree, others to the extent that one must wonder if any part of them was ever human."

The idea of a nocturnal, supernatural carnival attraction obviously traces back to the dark-fantasy work of Ray Bradbury ("The Black Ferris," Something Wicked This Way Comes). And the various contributors to the anthology--including such eminent genre writers as Neil Gaiman, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Gene Wolfe, S.P. Somtow, and Peter Crowther--furnish narratives that leave no doubt that this uncanny carnival ride would be right at home in the Cooger and Dark Pandemonium Shadow Show.

Unsurprisingly, the anthology is dedicated to Ray Bradbury ("Life is but a carnival and you are ringmaster to us all"). Moreover, the book contains a 51-line poem by Bradbury himself. "Death Has Lost Its Charm For Me" presents a speaker whose real-life brushes with human mortality have forced him to mature beyond an affection for the make-believe monsters and horrors (e.g., The Phantom of the Opera, King Kong) so beloved in boyhood. The sorts of fantastical figures that early teenagers like Jim Nightshade and Will Halloway might innocently admire. Bradbury's poem can be seen as forming a coda to Something Wicked This Way Comes, a novel that ultimately is less an attempted immortalizing of adolescence than an acknowledgment of the inevitably of aging--of transitioning from innocence to experience (Recall the foreboding line that concludes the novel's prologue: "And that was the October week when [Jim and Will] grew up overnight, and were never so young any more...").

Strange Attraction illuminates the manifold lines of influence extending from Bradbury to later fantasy/horror writers (and artists), but it's the lines of Bradbury's own poetic entry that link most intriguingly with the author's classic dark-carnival novel.

"Crowded After Hours"

by Lisa Snellings

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

QuickList: My Six Favorite Episodes of the Ray Bradbury Theater

The complete, 5-disc series of The Ray Bradbury Theater features 65 episodes, but these are the half-dozen that I remember most fondly:

*"The Playground": not even William Shatner's hammy acting could detract from this ultra-creepy episode. Sometimes kids do the damnedest things.

*"The Town Where No One Got Off": the title suggests an epidemic of sexual frustration, but the episode (starring a well-cast Jeff Goldblum) proves an unnerving tale of rural unfriendliness.

*"Skeleton": Eugene Levy is an excellent choice for the role of a hypochondriac who grows obsessed with his own fossil framework. Mr. Munigant and his dark office, meanwhile, are enough to chill anyone to the bone.

*"The Black Ferris": Imagine Something Wicked This Way Comes compressed into an eerily atmospheric short film. For some reason, the guy operating the titular ride freaks me out even more than Mr. Cooger himself.

*"Mars is Heaven": Shows that the Red Planet can also be the home of American Gothic. It's a testament to Bradbury's genius that a simple line like "But you're not thirsty" can have such terrifying effect.

*"Usher II": An episode steeped in medieval Gothicism. It offers plenty of plot twists as well, and scenes of vengeance that would make Poe proud.

Labels:

QuickLists,

Ray Bradbury Month

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Instant Halloween Party--The Encore Set

Last year at this time I composed a post entitled "Instant Halloween Party," which embedded 31 holiday-appropriate YouTube videos (that crossed eras and genres and ranged beyond the standard selections). If you are looking for some more theme music for this year's Halloween festivities, you can click on this post and enjoy the following encore set of 13 songs.

1.First, some mood music...And since it's Ray Bradbury Month here at Macabre Republic, what better place to start than with "Something Wicked":

2.And you thought carols were just for Christmastime:

3.There's a reason this Nick Cave classic was included in the Scream movies--it's so wonderfully creepy:

4.Some haunting crooning, courtesy of Sarah McLachlan:

5.Yes, Halloween is celebrated even in Margaritaville:

6.Don't kick off those dancing shoes yet:

7.Rihanna meets Michael Jackson in this infectious Halloween pop song by China McClain:

8.The caged beasts are all riled up and looking to get out tonight, as Halloween declares prohibition on inhibition:

9.Greetings from Chuck D.:

10.Black No. 1 (and orange a close second)

11.Did anyone order some gore?

12.The popularity of the walking dead is through-the-coffin-lid this year, but this Zombie is big every Halloween:

13.Who cares if it is after midnight--All Saints' Day can wait 'til dawn:

1.First, some mood music...And since it's Ray Bradbury Month here at Macabre Republic, what better place to start than with "Something Wicked":

2.And you thought carols were just for Christmastime:

3.There's a reason this Nick Cave classic was included in the Scream movies--it's so wonderfully creepy:

4.Some haunting crooning, courtesy of Sarah McLachlan:

5.Yes, Halloween is celebrated even in Margaritaville:

6.Don't kick off those dancing shoes yet:

7.Rihanna meets Michael Jackson in this infectious Halloween pop song by China McClain:

8.The caged beasts are all riled up and looking to get out tonight, as Halloween declares prohibition on inhibition:

9.Greetings from Chuck D.:

10.Black No. 1 (and orange a close second)

11.Did anyone order some gore?

12.The popularity of the walking dead is through-the-coffin-lid this year, but this Zombie is big every Halloween:

13.Who cares if it is after midnight--All Saints' Day can wait 'til dawn:

HAPPY HALLOWEEN!!!

Labels:

Halloween Season,

Ray Bradbury Month

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#3

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#3."The October Game" (collected in The Stories of Ray Bradbury)

"White bone masks and cut pumpkins and the smell of dropped candle fat" help set the scene in this 1948 story that takes place on Halloween. Viewpoint character Mich Wilder, though, doesn't relish the holiday, associating it with the waning of the year. In fact, Mich (who today would probably be diagnosed with Seasonal Affective Disorder) "had never liked October. Ever since he first lay in the autumn leaves before his grandmother's house many years ago and heard the wind and saw the empty trees. It had made him cry, without a reason. And a little of that sadness returned each year to him. It always went away with spring."

In this stone-cold Tale from the Crypt, Mich plots to make his frosty wife Louise suffer by taking their 8-year-old daughter Marion away from her. "The October Game" climaxes with a party activity in the darkened cellar of the Wilder home: the ostensible body parts of a dismembered witch (e.g. chicken innards traditionally stand in for human viscera) are passed around piece-meal. The scene brims with suspense, as Louise steadily grows more horrified over her daughter's strange silence. Marion, she realizes, is present only in body (not mind and spirit), because Mich has proven a fiend for realism when staging this party-ending game.

Mich's machinations lead to a shocking conclusion (and a classic final line), but upon re-reading one also appreciates just how carefully Bradbury has prepared for this ending. Foreshadowing abounds, from a "nasty childish game" Mich plays with Louise earlier in the day, to the "skeletonous" costume Marion dons for the Halloween party. "The October Game" is doubtless the grisliest piece of short fiction Bradbury has ever written (these days the author himself shies away from the narrative's filicidal violence), but it is simultaneously a masterpiece of technique. When it comes to dramatizing a husband's maniacal scheme, Bradbury is crafty indeed.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Macabre in the Blogosphere: October Country

Blu Gilliand is a rising writer in the horror genre, and an interviewer extraordinaire. He also writes the blog October Country, which takes its name from a certain short story collection. So it's only natural that I highlight Blu's blog during Ray Bradbury Month here at Macabre Republic. Rest assured, there's some fun stuff being posted at October Country this Halloween season, including the on-going features "Ten Essential October Comics" and "Ten Essential October Reads" (hardly a spoiler: Bradbury's work makes the latter listing).

I encourage you to click on over and take your autumnal tour...

I encourage you to click on over and take your autumnal tour...

Monday, October 24, 2011

Ray Gets Risque?

"A great brambly cat flashed by Tom's cheek. He felt a wooden pole between his legs jump up."

No, not some tale about a perverted ailurophile, but the most unintentionally funny lines Ray Bradbury ever wrote. This short paragraph (which sounds even more lurid when taken out of context) actually comes from the scene in The Halloween Tree where the boys are swept up by "the gathering of the Brooms."

Let's face it: the name Ray Bradbury and erotica just don't mix. That's what makes Rachel Bloom's comic-homage music video,

"F**k Me, Ray Bradbury," so hysterical. When I first caught the video last year, I thought it was a bit offensive, but then learned that the nonagenarian Bradbury himself got quite a kick out of the spoof. It just goes to show that you can't judge a book by its cover, or an author's sense of humor by his relatively chaste fiction.

The content of "F**k Me, Ray Bradbury" is a little too adult for me to feel comfortable about embedding the video here (imagine a sexed-up version of Britney Spears's "Baby One More Time"), but it can easily be found on YouTube. (Be forewarned, though: the song will get stuck in your head, and you might catch yourself echoing its lascivious chorus at the most inappropriate times!)

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#4

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#4."The Jar" (collected in The October Country)

Carousels, Ferris wheels, mirror mazes: Ray Bradbury has featured them all in his dark-carnival fiction, and in "The Jar," the author draws on the freak show staple of the pickled punk. The story's protagonist, Charlie, purchases the titular object from the boss of a carnival traveling deep through the heart of Louisiana. Charlie has been utterly captivated by the enigmatic carcass preserved within the container. As Bradbury writes in the incredible opening paragraph:

It was one of those things they keep in a jar in the tent of a sideshow on the outskirts of a little, drowsy town. One of those pale things drifting in alcohol plasma, forever dreaming and circling, with its peeled, dead eyes staring out at you and never seeing you. It went with the noiselessness of late night, and only the crickets chirping, the frogs sobbing off in the moist swampland. One of those things in a big jar that makes your stomach jump as it does when you see a preserved arm in a laboratory vat.The jar is placed on the mantle on Charlie's home, and the farmer's rural neighbors soon make a habit of coming to visit so that they can get a good look at the contents. A quintessential conversation piece, the jar prompts the gathered folk to speculate about the nature of the thing floating within. Their theories range from the ridiculous to the sublime, yet every observer seems to sense a deeper significance: "From the shine of their eyes one could see that each saw something different in the jar, something of the life and the pale life after life, and the life in death and the death in life."

Bradbury opts for an E.C.-Comics-style ending, with Charlie filling the jar with the decapitated head of his heckling, cuckolding wife. But by closing the narrative with a repetition of the opening paragraph, the author demonstrates that his concerns lie more with profundity than shock value. The bracketing effect created by the reiterated paragraph underscores the notion that Bradbury's story is itself a jar brimming with dark mystery. And much like Charlie and company, readers can't help but to give this jar their rapt attention, even as their "secret fear juice" is frothed by it.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Ray's Vectors: The Black Carousel

[For the previous vector, click here.]

Anyone familiar with the work of the late, great Charles L. Grant knows that strangeness abounds in the small town of Oxrun Station, Connecticut. Perhaps the only thing that could make this inherently American-Gothic burg any creepier is the arrival of a dark carnival. And that's just what happens in Grant's 1995 collection of four linked novellas, The Black Carousel (whose very title hearkens back to Ray Bradbury's "The Black Ferris," the short story precursor to Something Wicked This Way Comes).

The itinerant carnival known as "Pilgrim's Travelers" has visited Oxrun Station sporadically over the years, setting up its putative amusements on the grounds of an abandoned farm. Lurking in its shadowed heart is the eponymous ebon carousel. But this is no Cooger-and-Dark knock-off: the ride is no time machine causing maturation or rejuvenation based on the direction of its spin. The black carousel makes a misnomer of the "merry-go-round," as its dizzying spin and haunting music warp reality and deliver passengers to the world of worst nightmares.

It's hard to say whether Pilgrim's Travelers is eerier when it is bustling with activity at night or when it is shut down during daylight hours. Whichever the case, the narrator of the book's frame story paints an unforgettable image of desolation when ruminating about carnivals and fairs:

Flares themselves, but blinding for a night or a weekend and just as swiftly gone, leaving behind nothing but an empty field, a blowing wind, tracks in the earth, and the smell not of cotton candy and candied apples, not of grease-paint and grease, but of a slow smiling dying.

The way a carousel sounds when the last tune's been played and the animals stop spinning.Grant seizes upon Bradbury's fair-is-foul motif, but offers no identifiable carnival proprietor, no equivalent to Mr. Dark or Mr. Cooger (nor does any troupe of frightfully freakish underlings make appearance). This seeming lack of attendants at Pilgrim's Travelers, though, only accentuates the ominousness of the attractions themselves. For those who like their horror more unnerving than shocking, The Black Carousel provides one helluva ride.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Friday, October 21, 2011

Something Wicked This Way Comes (Graphic Novel Review)

Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes: The Authorized Adaptation (Hill and Wang, 2011)

It seems to me that a graphic novel must be judged along two fronts--the narrative running through its pages and the artwork filling its panels. In regards to the former, this volume does an impressive job of adapting Ray Bradbury's classic novel. The plot is preserved, will all the key scenes translated to the new medium. Even better, passages of of Bradbury's poetic prose have been interspersed throughout, recreating the atmosphere of the original novel.

Ron Wimberly's drawings, however, are a mixed bag. For sure, there are some stunning visuals, such as the sight of the Dust-Witch's black balloon crossing in front of the moon. Yet there's also a sense here of missed opportunity--the carousel is nondescript, and Mr. Dark (his large mustache giving him the look of Daniel Day-Lewis in Gangs of New York) is a man only faintly Illustrated, his tattoos conveyed as chiaroscuro blurs. The biggest problem, though, is that black-and-white just doesn't do justice to Bradbury's dark carnival (if ever there was a graphic novel begging to be splashed with autumnal colors...).

Still, I don't hesitate to recommend this book, which will certainly appeal to fans seeking a new taste of an old favorite. And for younger readers not quite ready to tackle the full-length novel, this graphic adaptation can meantime serve as a wonderful primer.

Labels:

Book Reviews,

Ray Bradbury Month

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#5

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#5."The Dwarf" (collected in The October Country)

Much like Bradbury's other carnival tales, "The Dwarf" (first published in 1954) prefigures Something Wicked This Way Comes--especially in its focus on a Mirror Maze. But there are also some salient differences between story and novel. For one thing, the carnival in "The Dwarf" is set atop a sunny seaside pier, not in some autumnal meadow in the Midwest. More importantly, in the short story Bradbury substitutes gritty realism for supernaturalism, dark crime for dark fantasy.

The titular dwarf, Mr. Bigelow (brilliantly described as "resembling nothing more than a dark-eyed, dark-haired, ugly man who has been locked in a winepress, squeezed and wadded down and down, fold on fold, agony on agony, until a bleached, outraged mass is left, the face bloated shapelessly") habitually pays a dime to enter the carnival's Mirror Maze. In the back room of the attraction, Bigelow can be spied dancing happily before his enlarged reflection in one of the special mirrors. What at first might seem like a touching narrative, though, quickly shades off into noir.

Good-hearted Aimee (who operates the carnival's "hoop circus") feels kindly toward the diminutive figure and seeks to help him. Trying to learn more about him, she discovers that Bigelow is a writer who pounds out "pulp detective stories" all night long in his "one-room cheap apartment." Aimee admires the man's talent and believes he could be quite a successful scribe if he had more self-confidence. Thinking that Bigelow would be better off if he didn't have to make his ignominious trips to the carnival (where the Mirror Maze's attendant, Ralph, always looks down on him), Aimee arranges to have a replica of the image-lengthening mirror sent to the his apartment. But Ralph, contemptuous of Aimee's benevolence and perhaps jealous of her attention to the dwarf, in the meantime rigs the Mirror Maze so that it gives Bigelow a distorted reflection of a much different sort. This cruel trick ultimately spurs the dwarf to take murderous revenge against Ralph.

When last seen, Bigelow is a "horrid" figure who sends Aimee running scared, but Bradbury's story labors to show that the poor man was pushed to such a criminal low. In "The Dwarf," the ostensibly "normal" Ralph is the true monster, his attitudes/actions proving more grotesque than any freak deformity of physique.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Bradbury Shelves

"The Bradbury Shelf": the phrase was coined by writer Norman Partridge, who in a post last year on his blog American Frankenstein talked about the intro to the TV series The Ray Bradbury Theater (where Bradbury steps into an office filled with objects that fire his imagination). Partridge's own version of a story-inspiring "Bradbury Shelf" is pictured above, and here below is the intro for the TV show. Following that is a picture of my own (relatively modest) shelf, which is topped mostly with Extreme Headknockers and painted plaster molds cast from the Gabriel Monster Machine.

So what's on your Bradbury Shelf? (Or better: what would you like to have on it?)

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Ray's Vectors: "Mr. Dark's Carnival"

[For the previous vector, click here.]

In its very title, Glen Hirshberg's 2000 novella (collected in The Two Sams: Ghost Stories) signals its allegiance to Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. Set in a modern-day prairie town on October 31st, the tale centers on "the legendary, mystery-shrouded Carnival-to-end-all-Carnivals." As Hirshberg's college-professor narrator relates, Mr. Dark's Carnival is "the inspiration for all our Halloween festivities, the most celebrated attraction or event in the history of Clarkston, Montana."

None of the Halloween-loving folk of Clarkston are certain that Mr. Dark's Carnival ever even existed (nor does anyone know why it is actually labeled a carnival). The life of the historical figure Albert Aloysius Dark ("Born God-knows-where, educated God-knows-where") is likewise cloaked in shadow. Apparently the man was a late-19th Century judge with a penchant for handing out dubious guilty verdicts and then personally presiding over the hangings of the victims. Such ghoulish reputation turns Judge Dark into the local bogeyman for later generations of Clarkstonians; he's reputed to drift around the prairie in his black robe, seizing on livestock and scaring to death anyone unfortunate enough to glimpse him. When it comes to sinister, Bradbury's Illustrated Man has nothing on this Mr. Dark.

The novella's eponymous amusement proves more fright-filled funhouse than traditional carnival (although there is a wonderfully ghastly game-booth stationed in the yard). Hirshberg puts the haunt in haunted attraction, but just when the reader thinks he/she has a handle on the situation and has safely navigated the narrative, the author gives a final turn of the screw that's no less chilling than the snow-swept prairie landscape the characters traverse.

"Mr. Dark's Carnival" is a classic work of Halloween literature, and ranks among the finest of homages to Bradbury's novel ever penned. And muck like Something Wicked This Way Comes, it is a work that invites re-reading each year as late October is gripped in autumnal chill.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Monday, October 17, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#6

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#6."Heavy-Set" (collected in Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales)

"A good Halloween party, with all the apples he took along, and the apples, untied, to bob for in a tub of water, and the boxes of candy, the sweet corn kernels that really taste like autumn....[E]veryone whirling about in costumes, and all the pumpkins cut, each in a different way, and a contest for the best homemade mask or makeup job, and too much popcorn to eat." At first, this all sounds like traditional holiday fare, but the story that unfolds in Bradbury's 1964 tale "Heavy-Set" quickly veers away from normality.

For starters, the planned Halloween party turns out to be a disaster: none of the handful of people who actually show up even bother to dress in a costume. No games are played, and couples soon leave the shack on the pier to go walk by themselves down the beach. Bitterly disappointed, the party's host, Leonard, returns home to sulk.

Thirty-year-old Leonard (also called "Heavy-Set," "Sammy," "Butch,"

"Atlas," and "Hercules" by the high-school boys) is a physical specimen but a social misfit. A loner who would rather work out with his weights than go out on dates with girls. His is a case of arrested development, as symbolized by the "mean little kid" outfit he wears to his Halloween party. The source of his problems is perhaps his clingy, single mother, who at one panicky point

imagines that Leonard will meet someone at the party and never come back home to her again. Maybe the knowledge that his mom depends on him is the real reason Leonard spurns romance. One thing is for certain: Freud would have a field day with this parent-child relationship.

"Heavy-Set" is the most understated and ambiguous of Bradbury's Halloween tales. Is Leonard laughing or crying to himself at tale's end? Has he climbed into his mother's bed in the middle of the night seeking solace or planning violence? The story ends with the mother worrying that if Leonard ever stops squeezing those hand grips he's always working, he might seize upon something less

pliable (like her throat). And in the very last line, Bradbury notes that it was "a long time before dawn"--an appropriately dark note on which to conclude this haunting narrative.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Beelzebub Tweets

BLZ, Bub

[For previous tweets, click here.]

Something Wicked This Way Comes: I wonder if Bradbury would mind if I had that printed on my business cards.

--7:40 P.M., October 15th

The scene where Mr. Dark trashes the King James Bible in the Green Town library. That's what we call canonical literature Down Below.

--11:32 A.M., October 13th

Remember, October Gamers: there's no substitute for realism.

--12:06 A.M., October 10th

Beloved the autumn people--fallen as the fire-colored leaves scratching across the macadam.

--9:49 P.M., October 5th

Loosen up enough nuts and bolts, and any amusement park becomes a dark carnival.

--3:00 A.M., October 1st

Labels:

Poetry/Flash Fiction,

Ray Bradbury Month

Saturday, October 15, 2011

Anatomy of a Weird Tale: "The Scythe"

Technically, Ray Bradbury's story "The Scythe" (first published in 1943) is set in April and May, but its concern with grim reaping also locates it within the heart of the October Country. This is a perfect time, then, to take a closer look at the workings of Bradbury's classic tale.

Ominousness is immediately invoked, as the story's opening sentence conveys a sense of the end of the line: "Quite suddenly there was no more road" (175). Drew Erickson--a farmer deracinated by Dust Bowl exigencies--and his starving family have driven up to a lone white house flanking a broad wheat field. Hoping to get some food from whomever lives in the place, Drew sets out from his car but even as he crosses the threshold he knows "there was death in the house" (176). He discovers an old man, apparently recently deceased, stretched out on the bed in his grave clothes, clutching a single, ripe blade of wheat. A scythe leans up against the well next to the dead man's bed, seeming less an inanimate tool than a looming presence that has been keeping vigil.

On the pillow next to him, the late John Buhr has left his last will and testament. The house and farm are bequeathed to the reader of the letter, as are the scythe and "the task ordained thereto" (177). Curiously, Buhr concludes by pointing out that he's "only the giver, not the ordainer." Meanwhile, the sickle blade of the scythe bears the enigmatic engraving "WHO WIELDS ME--WIELDS THE WORLD." The Erickson family has stumbled upon a dramatic reversal of fortune, but Drew's wife Molly is understandably wary about the impromptu inheritance: "It's too good to be true," she asserts. "There must be some trick to it."

Drew, though, is the first to discover that there is indeed a catch. The wheat field proves to be no ordinary piece of real estate, growing

"crooked, wild, like a crazy thing" (181). Its irregular clusters of ripe stalks rot soon after being cut, only to be replaced by fresh green sprouts the next morning. In the midst of his reaping labors, Drew is haunted by "sad voices" begging him to stay his hand, and to his horror he instinctively feels that he has committed accidental matricide with a swipe of his scythe. "I cut down one stalk of wheat and I killed her," a frantic Drew relates to Molly. She dismisses his concern as silly superstition, but then a letter arrives in the mail a week later notifying Drew of his mother's death from heart failure.

Typical of Bradbury's work, a metaphor has been given a literal (and dire) turn: Drew is a reaper not just of wheat but of human lives meta-physically linked to the stalks. The agricultural landscape accordingly transforms into a site of Lovecraftian "cosmic dread" (note as well how Bradbury's tale prefigures Stephen King works such as "Children of the Corn," Pet Sematary, and "N."). Drew blanches at the thought that the terrible power of this preternatural field stretches back through prehistory:

Quite suddenly he felt very old. The valley seemed ancient, mummified, secretive, dried and bent and powerful. When the Indians danced on the prairie it had been here, this field. The same sky, the same wind, the same wheat. And, before the Indians? Some Cro-Magnon, gnarled and shag-haired, wielding a crude wooden scythe, perhaps, prowling down through the living wheat... (183-4)In many narratives, the revelation of the wheat field's sublime aspect might have served as the climax, but Bradbury wrests more mileage (or should I say, acreage?) out of the premise. Compelled to provide food and shelter for his family, Drew continues on at the farm. He mows the wheat down methodically: "Up, down. Up, down. Obsessed with the idea of being the wielder of the scythe. He, himself! It burst upon him in a mad, wild surge of strength and horror" (184). Along with this sense of personal import, though, is Drew's realization of the burden of incredible responsibility. "I got to stay here all my life," he tells Molly. "Can't nobody else mess with that wheat; they wouldn't know where to cut and not to cut. They might cut the wrong parts." With this, an earlier line from John Buhr's will--"alone in the world as it has been decreed" (176, italics mine)--takes on frightful new meaning.

Drew tries to be smart about his predicament. He decides that whenever he comes to the stalks corresponding to the lives of Molly and the kids, he will just leave that wheat standing. Yet when he brings death "to three of his old, loved friends in Missouri" (185), Drew vows to put aside the scythe. He "was done with reaping, done for good and all," he insists as he locks the scythe in the cellar.

In the middle of the night, however, Drew discovers that his duty is not easily shirked; the harvesting must go on. He awakens to find that he has sleep-walked out into the field, and his scythe is now back in hand. The somnambulistic trek unveils Drew's utter lack of free will. He is a slave to the ordained task, controlled by the very instrument he wields: "The scythe held him, grew into his palms, forced him to walk" (186). The scenario worsens when Drew looks back and sees his farmhouse engulfed by flames. The place is a smoldering ruin by the time he races back, but his family lies

haphazardly, leveling green and ripe wheat alike. Here the most harrowing aspect of Bradbury's tale emerges, as the author posits an uncanny cause for the widespread ills of the mid-20th Century world:

Bombs shattered London, Moscow, Tokyo.

The blade swung insanely.

And the kilns of Belsen and Buchenwald took fire.

The blade sang, crimson wet.

And mushrooms vomited out blind suns at White Sands, Hiroshima, Bikini, and up, through, and in continental Siberian skies.

The grain wept in a green rain, falling.

Korea, Indo-China, Egypt, India trembled; Asia stirred, Africa woke in the night... (189)The notion of mass death precipitated by a singular madman (cf. Adolf Hitler's maniacal warmongering) is one that no doubt resonated with Bradbury's contemporary audience.

"The Scythe" has been famously lampooned by The Simpsons (the

"Reaper Madness" segment of Treehouse of Horror XIV), but there's no denying the gravitas of Bradbury's original tale. It cuts straight to the heart of our worst dreads--of losing our loved ones, of having no control over our own fates. I would venture to say that never in his illustrious career has Bradbury presented his readers with a darker harvest.

Work Cited

Bradbury, Ray. "The Scythe." The October Country. New York: Del Rey Books, 1991.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#7

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#7."Let's Play 'Poison'" (collected in Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales)

Perhaps the most overlooked piece in Bradbury's autumnal oeuvre is this weird tale first published in November 1946. Traumatized by the tragic fall of one of his students from a third-story window, schoolteacher Mr. Howard moves away to Green Bay and settles into "self-enforced retirement." When finally coaxed into returning to work as a substitute teacher seven autumns later, he tyrannizes his new charges, calling the children "invaders from another dimension" and "little monsters thrust out of hell." Adopting the role of neighborhood curmudgeon, Howard also chases the students away whenever he finds them cavorting outside his house. The kids seem particularly fond of "playing poison," a macabre bit of make-believe involving cement sidewalks.

These sidewalks are conspicuously littered with autumn leaves, and Bradbury further weaves in a sense of season when describing the mounting tension between Howard and his pupils: "the silent waiting, the way the children climbed the trees and looked at him as they swiped late apples, the melancholy smell of autumn settling in around the town, the days growing short, the night coming too soon." Also, in the story's climax, the children's harassment of Howard (via a white skull raised to and tapped at his window) can easily be seen as an act of mischief laced with Halloween spirit.

When Howard is lured outside by the pranksters, he soon discovers that for some people, "playing poison" is no fun at all. Readers who think that Bradbury's writing is all about paeans to childhood are in turn forced to realize that the author has never been afraid to explore the sinister side of prepubescence. Kids can be so cruel sometimes, and sometimes Bradbury uses that fact to horrific effect.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Ray's Vectors: Halloweenland

[For the previous vector, click here.]

Al Sarrantonio, an October countryman who's scripted countless tales and novels set in the Halloween season, has long been hailed as a literary heir to Ray Bradbury. But Sarrantonio's influence by Something Wicked This Way Comes has never been more evident than in the 2007 novel Halloweenland.

A Halloween-themed carnival arrives in Orangefield--the pumpkin capital of the country, and locus classicus of "weird shit" (in the words of Detective Bill Grant)--and sets up on the outskirts of town. "Halloweenland" sports an incredible freak show, a monstrous, looming Ferris wheel, and a carousel whose horses look to be screaming in pain (the ride also features more outre figures such as a dragon, a gryphon, and Cerberus). The carnival's mysterious impresario goes by the singular, devilish name of Dickens (shades of Bradbury's infernal Mr. Dark). Sarrantonio, though, isn't content to merely echo Something Wicked; Dickens

proves to have a past history with Orangefield, and Halloweenland ultimately has an agenda other than simple amusement, but Sarrantonio still manages to offer some unique twists on the dark-carnival motif. All I'll give away here is that Dickens's haunted attraction forms the site of a stunningly apocalyptic climax late at night on All Hallows Eve.

As the concluding book of a trilogy (following Hallows Eve and Horrorween), Halloweenland is best read in sequence. But the novel's true touchstone is Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the deep orange sparks produced by Sarrantonio's strategic rubbing could light the largest jack-o'-lantern imaginable.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Post-Pandemonium (flash fiction)

Post-Pandemonium

Unfixed handbills ghosting through the depopulated streets. In the air, the mixed scent of cotton candy and vomitus. On the dead-grassed commons, a long, lone strip of sawdust, blood-speckled.

A formerly-green town left brown and forlorn. And no sign of the party responsible, save for the line of ashen puffs rising above the leafless treetops of the outlying woods--and the unlikely sound of calliope music dopplering off into the October night.

Something wicked that way goes.

Labels:

Poetry/Flash Fiction,

Ray Bradbury Month

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#8

(For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.)

#8."Homecoming" (collected in The October Country)

Halloween is the ultimate carnivalesque holiday, with its rituals of inversion valorizing darkness and chaos, mischievousness and unchecked impulses. Ray Bradbury captures this spirit of autumnal misrule in his 1946 short story "Homecoming." The tale presents an unprecedented monster bash, as scores of creatures travel from the old country to a Gothic manse in mid-American October country for a Family reunion on Allhallows Eve. These various vampiric and shape-shifting figures embody the idea of the inverse, sleeping by day in coffins, and moving their hands in "reverse blessings" while worshipping in a cellar chapel. The great house is decorated for the celebration with black crepe and "burning black tapers," and the party involves waltzes to "outlandish music" and imbibing from a blood-filled punch bowl (not to mention playing a most challenging game of Mirror Mirror--considering that many of the Family members don't even cast reflections!).

The story's prime example of turnabout, though, is its fourteen-year-old protagonist, Timothy. His natural humanity actually renders him the abnormal one in this Family (much like Marilyn Munster is considered the ugly duckling of her TV clan). Timothy sleeps in a regular bed, has "poor inadequate teeth" that will never elongate into fangs, dislikes the taste of blood, and fears the dark. Accordingly, he's treated like the white sheep of his Family, teased by his younger relatives, ignored by many of the older ones (not including the wonderful, winged Uncle Einar).

Bradbury puts the emphasis on sentiment rather than suspense in this bittersweet narrative. For all their fantastic revelry, the attendees of the reunion depart facing the daunting reality that "the world was becoming less a place for them." And Timothy ends the tale in tears, haunted by the understanding that his own mortality will inevitably distance him from his supernatural kin. Still,

"Homecoming" is a moving exploration of difference, a story that suggests that normality is always relative.

***

To read (in Bradbury's words) the "Life-Story of the Elliott Family: their genesis and demise, their adventures and mishaps, their loves and their sorrows," be sure to check out the author's 2001 book From the Dust Returned.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Monday, October 10, 2011

Halloween (Book Review)

Halloween, Edited by Paula Guran (Prime Books, 2011)

This new anthology is stocked strictly with reprints, but offers some lesser-known modern masterpieces (e.g., Charlee Jacobs's "The Sticks," Gary McMahon's "Pumpkin Night") alongside the familiar classics (such as Thomas Ligotti's "Conversations in a Dead Language," William F. Nolan's "The Halloween Man," and Al Sarrantonio's "Hornets"). When making her selections, editor Paula Guran ranges across historical eras and presents tales that work in a variety of modes, from the humorous (Esther M. Friesner's "Auntie Elspeth's Halloween story") and the harrowing (Joe R. Lansdale's

"On a Dark October") to the sentimental (Charles de Lint's "The Universal Soldier") and the eerie (Steve Rasnic Tem's "Tricks & Treats: One Night on Halloween Street").

Guran herself contributes a fine introductory essay tracing the origins and cultural history of Halloween. Her editorial expertise also manifests in the (context-sketching, stage-setting) headnotes she provides for the individual pieces. (It must be pointed out, though, that Halloween suffers from some atrocious copy editing. The book is rife with errors--typos, superfluous and omitted words--that prove terribly distracting and ultimately disappointing in a tome aspiring to be a holiday treasury.)

Admittedly, some of the selections in the anthology fall flat. The poems by Lovecraft and Poe seem tangential to the book's theme, included here mostly for the writer's name value. But Halloween also has the distinction of being the first volume to include both Ray Bradbury's "The October Game" and F. Paul Wilson's "The November Game." Wilson's immediate sequel to the legendary Bradbury tale is a loving homage that simultaneously takes the storyline in a startling new direction (as the incarcerated child-killer Mich finds some gruesome additions to his prison meals). Anyone who has ever reveled in "The October Game" will not want to miss this utterly frightful follow-up.

Halloween is a bit of a mixed bag in terms of overall quality, but contains more than enough treats to keep readers sated all month long. There are several delectable tales that I deliberately have not cited in this review (because what would Halloween be without some surprises?). But just so you have an idea of what you will be sifting through, here's a listing of the anthology's contents:

INTRODUCTION, Paula Guran

CONVERSATIONS IN A DEAD LANGUAGE, Thomas Ligotti

MONSTERS, Stewart O'Nan

THE HALLOWEEN MAN, William F. Nolan

THE YOUNG TAMLANE, Sir Walter Scott

PORK PIE HAT, Peter Straub

THREE DOORS, Norman Partridge

AUNTIE ELSPETH'S HALLOWEEN STORY, Esther M. Friesner

STRUWWELPETER, Glen Hirshberg

HALLOWEEN IN A SUBURB, H.P. Lovecraft

ON THE REEF, Caitlin R. Kiernan

THE STICKS, Charlee Jacob

RIDING BITCH, K.W. Jeter

MEMORIES OF EL DIA DE LOS MUERTOS, Nancy Kilpatrick

HALLOWEEN STREET, Steve Rasnic Tem

TRICKS & TREATS: ONE NIGHT ON HALLOWEEN STREET, Steve Rasnic Tem

MEMORIES, Peter Crowther

ULALUME: A BALLAD, Edgar Allan Poe

MASK GAME, John Shirley

BY THE BOOK, Nancy Holder

HORNETS, Al Sarrantonio

PRANKS, Nina Kiriki Hoffman

PUMPKIN NIGHT, Gary McMahon

THE UNIVERSAL SOLDIER, Charles de Lint

NIGHT OUT, Tina Rath

ONE THIN DIME, Stewart Moore

MAN-SIZE IN MARBLE, E. Nesbitt

THE GREAT PUMPKIN ARRIVES AT LAST, Sarah Langan

SUGAR SKULLS, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

ON A DARK OCTOBER, Joe R. Lansdale

THE VOW ON HALLOWEEN, Lyllian Huntley Harris

THE OCTOBER GAME, Ray Bradbury

THE NOVEMBER GAME, F. Paul Wilson

TESSELLATIONS, Gary Braunbeck

Labels:

Book Reviews,

Ray Bradbury Month

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Fantastic Casting: The "Something Wicked" Remake

It's been nearly thirty years now since the release of the film version of Something Wicked This Way Comes, so perhaps the time has come for a remake. If the novel were to be lensed again, which of today's actors would be best suited to fill the main roles? I'll leave aside the characters of Will and Jim (who would likely be portrayed by a pair of as-yet-unknown child actors), but here are my choices for the rest of the cast...

Charles Halloway: Jason Robards has magnificent presence and did a fine job in the original; my only quibble might be that the actor was actually too old-looking to portray Will's fiftysomething father. My choice for the new Charles would be Liam Neeson (who has acquitted himself well in prior paternal roles, such as in Love, Actually). Alternatively: David Straithairn.

Tom Fury: In my mind, there's no actor better suited to embody Bradbury's lightning-rod salesman than Harry Dean Stanton (he even looks like Royal Dano from the original!).

Mr. Cooger: Ray Winstone no doubt has the brawn to play this menacing figure, the brute half of the Cooger & Dark tandem. His face also possesses the expressiveness needed for the scenes following Cooger's wizening by the carousel.

Mr. Dark: It would be hard to argue against Christian Bale in this plum role, but I'm going to think a bit outside the box here. George Clooney has the charm, swarthiness, and commanding voice to make for a brilliant Mr. Dark.

The Dust Witch: The original went glam by casting the beautiful Pam Grier, but for a more traditionally witchy figure one could not go wrong with Helena Bonham Carter. Moreover, the actress's real-life mate, Tim Burton, would be the ideal director for the remake (after seeing his vision of Halloweentown, imagine what he would do with the carnival-plagued Green Town).

So what do you think--a proper cast for the prospective remake? (If you can think of other actors who might make good choices for the roles, feel free to leave a Comment below.)

Labels:

Cinemacabre,

Ray Bradbury Month

Wicked's Way

An aged but still engaging Ray Bradbury discusses the journey of Something Wicked This Way Comes from page to screen:

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Countdown: Ray Bradbury's Top 10 Dark Carnival/October Country Stories--#9

Let's make it a double-post day...

(For the previous entry on the countdown, click here.)

#9."The Black Ferris" (collected in The Stories of Ray Bradbury)

Bradbury sets the scene and season instantly in this 1948 tale, with a short but unforgettable opening paragraph:

The carnival had come to town like an October wind, like a dark bat flying over the cold lake, bones rattling in the night, mourning, sighing, whispering up the tents in the dark rain. It stayed on for a month by the gray restless lake of October, in the black weather and increasing storms and leaden skies.This embryonic version of Something Wicked This Way Comes lacks the sophistication of the novel (the story reads a bit like a Hardy Boys narrative, as young Peter and Hank endeavor to foil a jewel heist by the carnival man, Mr. Cooger). But "The Black Ferris" is wonderfully atmospheric, excelling in its depiction of the dark and desolate state of the carnival grounds ("The midway was silent, all the gray tents hissing on the wind like gigantic prehistoric wings."). Also, a black Ferris Wheel (which can age or rejuvenate a rider, by spinning forward or backward) makes for a more sinister apparatus than a carousel (the centerpiece of the carnival in the novel). Bradbury further accentuates the creepiness of the short story by having the Ferris manned by a blind hunchback in a black booth. And the final line of the story (a shocking ending for any reader unfamiliar with Something Wicked) has all the macabre magnificence of the concluding image of an E.C. Comic.

Much like its titular thrill ride, "The Black Ferris" is a magical time machine that transports readers back to the start of Bradbury's career. This portrait of a dark fantasist as a young man reveals a writer of fertile, and fiendish, imagination--a scribe likely to be sending many other significant dispatches from the October Country.

Labels:

Ray Bradbury Month,

Top 10 Countdowns

Book vs. Film: Something Wicked This Way Comes

Today's edition of Book vs. Film compares Ray Bradbury's 1962 novel Something Wicked This Way Comes with the 1983 Disney film version (which Bradbury had a hand in scripting, although differences of creative vision developed between the author and director Jack Clayton).

The film version is visually splendid, a vibrant translation of Bradbury's poetic descriptions. Autumn colors suffuse panoramic shots, and the leaf-blanketed lane that runs in front of the protagonists' houses creates a distinct sense of season. The Disney touch is evident in the rendition of Green Town, the quintessential small, mid-American community. Idyllic to say the least, with its neatly landscaped town square and quaint shops lining the streets.

Perhaps due to budget limitations, though, some of the more striking aspects of Bradbury's novel are not included in the film. For instance, the Dust Witch doesn't travel via black hot-air balloon but rather in the form of an ethereal, pea-green smog (an effect more hokey than horrifying). One of the most thrilling scenes from the novel (Will's bow-and-arrow defense of his home as the Dust Witch hovers overhead and attempts to mark the roof with slimy sign) is thus nowhere to be found. But the harrowing scene movie-goers are presented instead almost makes up for this omission: the tarantula infestation of the bedroom makes Arachnophobia seem as innocuous as Charlotte's Web by comparison.

The scenes that do closely parallel the novel are well-executed, such as the extended sequence in the library in which Mr. Dark (finely portrayed by a then-little-known Jonathan Pryce) faces off with Charles Halloway (Jason Robards, in another inspired bit of casting) and tracks down Will and Jim in the stacks. Pryce's Mr. Dark makes for a chilling villain--never more evident than when he terrorizes Will's father while tearing pages out of a library book--but my biggest issue with the filmic figure is that there's little sense given that he is The Illustrated Man (whereas Bradbury's novel makes much ado about the carnival owner's tattoos).

When it comes to the climactic vanquishing of the antagonists, the movie's approach is more spectacular yet ultimately less satisfying than the novel's. The lightning-rod salesman Tom Fury's rushing impalement of the Dust Witch cannot match the scene in the book where Charles Halloway outwits Mr. Dark (by inscribing a smile onto a rifle bullet) and shoots down the Dust Witch in front of a crowd of onlookers. Similarly, the scene in which Mr. Dark is fatally aged by the whirl of the haywire carousel (a ride taken by his business partner, Mr. Cooger, in the novel) is stunning to behold but less clever than Dark's manner of defeat in Bradbury's book.

For me, the film falls shortest in its characterization of Will and Jim. The young actors chosen to play the boys give lackluster performances; Will comes across as prissy, and Jim's impishness is de-emphasized. More importantly, the novel's coming-of age theme ("And that was the October week when they grew up over-night, and were never so young anymore," Bradbury establishes at the close of the Prologue) is under-developed in the film, virtually reduced to the framing device of an adult Will narrating in voiceover.

The movie is undoubtedly entertaining, but fails to equal the novel for depth of characterization and breadth of theme. That's why, using the 10-point-divvy system (imagine 10 gold coins distributed on the opposing arms of a scale), I rank the two versions as follows:

Movie: 3

/

/

/

Book: 7

Labels:

Cinemacabre,

Ray Bradbury Month

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)