Macabre Republic

Where Lovers of All-American Gothic Reside

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Autumn Lauds: Poems for the Halloween Season

Hello again to everyone out there in the Land of the Red, Black, and Blue. Yes, it certainly has been a while since I posted here. Last October 31st, after thirty-nine months and 851 posts, I found myself suffering from utter blogger exhaustion. My intention was to take a break and resume posting in the new year, but work intervened, and then I had a brush with mortality back in March. I have also been giving my attention to a few projects, the first of which is finally complete. My book Autumn Lauds: Poems for the Halloween Season is now available for purchase from Amazon. Check it out (and then hopefully proceed to checkout); if you count yourself as a devout celebrant of October's high holiday, this is the book for you.

Happy Halloween '14 to all the residents of our Macabre Republic!

Labels:

Halloween Season,

Poetry/Flash Fiction

Thursday, October 31, 2013

The Jack-o'-Lantern Abecedarium: Halloween Gourds a la Gorey

It's been fifty years since twenty-six children perished at the hand of a single man. The sinisterly surnamed Edward Gorey, though, wasn't a notorious mass murderer but rather an esteemed writer/ illustrator whose 1963 masterwork The Gashlycrumb Tinies takes the subject of juvenile demise from A to Z. Gorey's depictions of death encompass the accidental (a tumble down a staircase) and the deliberate (strangulation by thug), the mundane (choking on a peach), and the bizarre (being devoured by mice). Some of the drawings show the youngsters facing imminent mishap, while others pose victims in postmortem ignominy.

The common denominator is dark humor: Gorey's titular Tinies jointly evoke the Victorian (in both name and dress), yet any notion of the prim and proper is ironically undercut within the context of a grim primer.

The Jack-O'-Lantern Abecedarium commemorates the golden anniversary of The Gashlycrumb Tinies in orange and black fashion, turning to popular late-October ritual. Pumpkin carving--Halloween's quintessential act of creative destruction--offers terrific opportunity for both self-expression and (if one's not careful) self-infliction. The following "alphabet book" might not be as rife with fatality as its precursor, but it does strive for the same macabre and mischievous sensibility. My goal has been to honor the spirit of the holiday season while paying homage to the ultimately inimitable Mr. Gorey.

The Jack-O'-Lantern Abecedarium commemorates the golden anniversary of The Gashlycrumb Tinies in orange and black fashion, turning to popular late-October ritual. Pumpkin carving--Halloween's quintessential act of creative destruction--offers terrific opportunity for both self-expression and (if one's not careful) self-infliction. The following "alphabet book" might not be as rife with fatality as its precursor, but it does strive for the same macabre and mischievous sensibility. My goal has been to honor the spirit of the holiday season while paying homage to the ultimately inimitable Mr. Gorey.

A is for Andrew,

Who wound up carving his hand, too.

B is for Beverly,

Who decorated oh so cleverly.

C is for Carson,

Who was obsessed with arson.

D is for Dylan,

Who tried to grow penicillin.

E is for Elyse,

Who carved the Mark of the Beast.

F is for Frances,

Who took one too many chances.

G is for Godric,

Who ate candy 'til he got sick.

H is for Herbert,

Who was a bit of a pervert.

I is for Ivor,

Who created an eyesore.

J is for Jordyn,

Who should've brought her gourd in.

K is for Kevin,

Who loved the movie Seven.

L is for Leif,

Who was the neighborhood thief.

M is for Maisie,

Who was just plain lazy.

N is for Nell,

Who never learned how to spell.

O is for Onyx,

Who depicted pumpkin colonics.

P is for Pryce,

Who was committed to vise.

Q is for Quinn,

Who caused a cave-in.

R is for Riley,

Who refused to make hers smiley.

S is for Siri,

Who venerated the eerie.

T is for Tate,

Who had a distinguishing trait.

U is for Ulysses,

Who considered his younger brothers sissies.

V is for Victoria,

Who favored phantasmagoria.

W is for Wilfred,

Who sympathized with the ill-fed.

X is for Xavier,

Who formed a model of misbehavior.

Y is for Yul,

Who was the kind to be cruel.

Z is for Zach,

Who gave his a practice whack.

Now you know your A, B, C's...

Go carve out some more like these.

Special thanks to Lisa S. for providing the illustrations.

Countdown: The Top 20 Joe R. Lansdale Works of Short Fiction--#1

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#1. "By Bizarre Hands"

A Southern Gothic shocker set on Halloween, "By Bizarre Hands" (1988; collected in High Cotton) is my easy choice for the top Joe R. Lansdale work of short fiction.

The story's viewpoint character is a spurious evangelist in the mold of Davis Grubb's Harry Powell (Night of the Hunter) and Flannery O'Connor's Manly Pointer ("Good Country People"). Preacher Judd travels to the home of the Widow Case when he learns that the woman has a mentally-challenged daughter. Judd has "a thing for retarded girls, due to the fact that his sister had been simple-headed, and his mama always said it was a shame she was probably going to burn in hell like a pan of biscuits forgot in the oven, just on account of not having a full set of brains." He also has "this thing for Halloween, because that was the night the Lord took his sister to hell, and he might have taken her to glory had she had any bible-learning or God sense." Regretting his sister's perdition, the now-adult Judd has devoted himself to "baptizing and giving some God-training to female retards" (but not "boys or men or women who were half-wits").

This preacher's mission is hardly a glorious one, apropos of a story that foregrounds grotesquerie. Judd's father ran off with a "beaver-toothed wash woman"; his Granny was killed and eaten by the family's hogs. Facially, Widow Case resembles a "shaved weasel," but the hair on her ankles is "thick and black enough to be mistaken for thin socks at a distance." The widow's drooling, ant-eating, knuckle-dragging daughter, meanwhile, has been incongruously christened Cinderella. Unabashed in its political incorrectness, Lansdale's narrative finds much of its comedy in Cinderella's imbecility. Not realizing the TV has been turned off, the girl watches "the dark screen like the White Rabbit considering a plunge down the rabbit hole." When Judd promptly baptizes her with drops of iced tea on head, "Cinderella held out her hand as if checking for rain." It's hard not to laugh at such lines, and even more difficult not to feel guilty for doing so.

The truest grotesque here, though, is Preacher Judd himself. Turns out, he was the one who raped and murdered his own sister on Halloween night all those years ago, leaving her lying with "her brains smashed out and her trick or treat bag turned inside out" (after discovering the body, naked beneath a white-sheet ghost costume, the local sheriff asserts that the girl was killed "by bizarre hands"). Judd's intentions for Cinderella are no less illicit, and his offer to take her trick-or-treating is a predator's lure. Beware of strangers without any candy.

When Widow Case finally catches wise to the situation, the fight that ensues between her and Preacher Judd takes black humor to an almost slapstick level (e.g. Judd distracts the widow by holding up his left hand and wiggling "two fingers like mule ears," then floors her with a right cross). But just as Judd's true colors come to light, so does the story's darker impulses. "By Bizarre Hands" exacts a tonal shift similar to the one in "Night They Missed the Horror Show": Lansdale hooks readers with humor then gut-punches them with grim horror. There's zero mirth to be found in the scene where Judd catches up with Cinderella (who ran off while he was fighting with her mother) and repeatedly brains her with a frying pan, the sound of the fatal bludgeoning like "hitting a thick, rubber bag full of mud." In "Night They Missed," the author ultimately offers a critical commentary on ignorant racism; here in "Hands," he tackles the human evil that parades around in holy clothing.

Preacher Judd possesses all the deluded self-righteousness of the putatively religious. As he drives away from the scene of his latest crimes at tale's end, he glances at the moon overhead and notes its resemblance to "a happy jack-o-lantern," which the Halloween lover takes as "a sign that he had done well." Every last paragraph in this wickedly entertaining and disturbing narrative is an indication of how well Lansdale himself has done. A signature piece, "By Bizarre Hands" is the work of an utterly masterful short story writer.

Labels:

Halloween Season,

Top 20 Countdowns

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Trick or Treat!

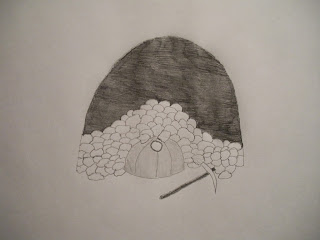

Hand over some candy while you still can. This gourd is ready to start carving if you don't satisfy its craving.

I decided to do an etching this year, partly because I just didn't have the heart to gut this picturesque pumpkin. That stem, by the way, is real (the vine arms were made by Ray Villafane); I love its witch's-hat shape, which gives a hint of mischievousness.

If you're a fan of jack-o-lanterns, be sure to check out the special post I have planned for tomorrow...

Labels:

Halloween Season,

Photesquerie

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Countdown: The Top 20 Joe R. Lansdale Works of Short Fiction--#2

[For the previous entry on the Countdown, click here.]

#2. "Master of Misery"

We've seen already on this Countdown that Joe R. Lansdale has a knack for channeling literary greats (without necessarily resorting to pastiche). In 1995's "Master of Misery" (collected in Bumper Crop), the author invokes a true heavyweight of American fiction, Ernest Hemingway. His hard-boiled tale of fishing, fighting, and other acts of machismo would certainly make Papa proud.

On a charter fishing boat in the Caribbean, protagonist Richard Young encounters a wedded couple who prove that love and marriage don't necessarily go hand in hand. The wealthy husband, Hugo Peak (the pinnacle of prick-dom) is cocky, obnoxious, and misogynistic, his trophy wife Margo beautiful yet abused. A long opening scene establishes the pair of characters fully, as Peak harangues and humiliates Margo after she unintentionally insults his male ego by landing a bigger fish than he did. Peak's behavior is blatantly repulsive, but by scene's end the reader learns there is more going on here than meets the eye. Richard has been lured onto the charter boat with the Peaks, and boorish Hugo has been trying to antagonize the man into fighting him. That's because Richard is a former world-champion kickboxer who retired from competition after killing his opponent with an illegal blow, and Peak (a trained Thai fighter) "was the kind of man who would want to know a man who had killed someone. He would want to know someone like that to test himself against him. He would see killing a man in the ring as positive, a major macho achievement."

When the initial baiting attempt on the fishing boat fails, Peak next sends a battered Margo to Richard's apartment with an ominous message: Peak will continue to beat her mercilessly if Richard does not agree to come to his private island for a square off. "He told me to tell you that he can be a master of misery," Margo relays. "If not to you, than to me." Richard scoffs at first at the whole sordid scenario ("the goddamn son of a bitch must think he's a James Bond villain"), but when he finally does accept the invite to fight Peak, it's not for the $10,000 prize or the promise of Margo as a bonus ("I got to be happy somewhere else besides below the belt," Richard sardonically informs the temptress when she assures him she knows how to make a man happy). No, the real enticement for Richard is the chance to commit unbridled violence once again. In an introspective moment, Richard acknowledges his primitive urges: "It was a scary thing inside of him; inside of humankind, mankind especially, this thing about killing. This need. This desire. Maybe, he got home, he'd go deer hunting this year. He hadn't been in over ten years, but he might go now. He might ought to go."

Richard's showdown with Peak is a pugilistic-rules-be-damned fight to the finish. The story waxes philosophical over such bloodsport, with Peak professing to his foe: "Death, it's nothing. You know what Hemingway said about death, don't you? He called it a gift." Literary allusion soon gives way to physical brutality, though, as Lansdale's expertly choreographed battle between the two male warriors features a slew of graphic detail. We get to feel the bones of the human skull cracking beneath a vicious heel kick, to hear an ear rip off the side of a head "like rotten canvas." And while the hurricane that breaks in on the climactic bout does smack of deus ex machina, it is also fitting, underscoring the notion of human wreckage. Indeed, Lansdale doesn't waste any blows in this story, with each sentence perfectly crafted to create narrative power. The end result--a tale defined by rich characterization, overtly dramatic

incident, vivid settings and strong themes. "Master of Misery" causes anything but unpleasantness for the captivated reader, furnishing a stunning reminder of why its author is the undisputed Champion Mojo storyteller.

Labels:

Top 20 Countdowns

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)