Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Countdown: The Top 20 Stephen King Works of American Gothic Short Fiction--#16. Premium Harmony

#16. "Premium Harmony"

[For previous entries, click the "Top 20 Countdowns" label under Features in the sidebar]

Note: King's short story was published in The New Yorker in November 2009. Those unfamiliar with it might want to read it first before proceeding with this blog post.

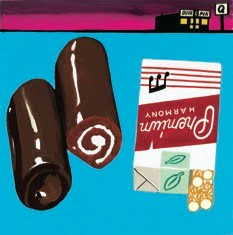

A decade together has drained the magic from Ray and Mary Burkett's marriage. Argument is now their primary form of communication, as seen on their drive through the economically-depressed town of Castle Rock. They are headed over to the Wal-Mart to buy some grass seed (King stocks the story with calculatedly banal detail) when Mary insists they stop off at the Quik-Pik so she can purchase a purple kickball for her niece. Tempers flare when Mary balks at buying Ray a pack of cigarettes; he proceeds to taunt her about her weight and her fondness for snack cakes. As the first scene closes, King brilliantly illustrates the petty animosity that results from a long life with a so-called loved one: Ray has "parked too close to the concrete cube of a building and she has to sidle until she's past the trunk of the car, and he knows she knows he's looking at her, seeing how she's now so big she has to sidle. He knows she thinks he parked close to the building on purpose, to make her sidle, and maybe he did."

Ray waits in the car with the family dog Biznezz, but is summoned inside by a worker minutes later after the thirty-five-year-old Mary drops dead of a heart attack. The scene inside the Quik-Pik is painted with blackly comic strokes, as Mary lies sprawled next to a kickball-filled wire rack whose sign proclaims "Hot Fun In the Summertime," and as the store manager Mr. Ghosh offers to drape a souvenir T-shirt ("My Parents Were Treated Like Royalty in Castle Rock and All I Got Was This Lousy Tee-Shirt") over Mary's face. Ray hardly comes across as a nobleman here; his thoughts are in turn lascivious (he speculates that if he returned to the store next week, the counter girl would "toss him a mercy fuck"), racist (he isn't thrilled by the idea of the dark-skinned Mr. Ghosh performing artificial respiration on Mary), and insensitive (he believes a woman standing there holding a bag of Bugles should be the one lying on the floor, since she's even fatter than Mary).

Basking in his "celebrity" status as a sudden widower, Ray lingers in the store after the ambulance leaves with his wife's body. He drinks soda, eats some Bugles, and converses with the other customers and the store employees before finally disembarking. Returning to his car nearly two hours after first pulling up at the Quick-Pik, Ray is greeted by another corpse: the forgotten Biznezz is now lying belly-up in the backseat, killed by the sweltering heat. "Great sadness and amusement sweep over [Ray] as he looks at the baked Jack Russell"; he starts to cry and bemoans his double loss, but he might just be going through the motions (he thinks that "[i]t's a relief to sound just right for the situation"). Ray's mixed reaction here in the conclusion underscores the ambivalence that lies at the heart of King's understated story. The reader is left to ponder: is Ray simply contemptible, or just a common man, humanly flawed? That unsettling second possibility is what transforms "Premium Harmony" into an intriguing work of American Gothic fiction.

Labels:

Top 20 Countdowns

Monday, August 30, 2010

Carnivale Revisited--Episode 1: "Milfay"

The dramatic series Carnivale, a Steinbeck-meets-Bradbury hybrid chronicling a traveling carnival in mid-1930s Dust Bowl America, aired for two seasons on HBO from 2003-2005 before being unceremoniously cancelled (a decision that I, and many other of the show's loyal fans, never forgave the network for). "Carnivale Revisited" will be a recurring feature here on Macabre Republic in which I post episode guides for what is arguably the greatest (non-anthology) dark fantasy series in the history of television. The guides will offer an overview of the individual episodes rather than scene-by-scene summaries rife with plot spoilers. My hope is to stir some fond memories for those who watched the show faithfully, and to spur those unfamiliar with the series to fill up their Netflix queues or purchase Carnivale: The Complete First Season on DVD. I'll begin today by covering the show's debut episode, "Milfay."

The episode introduces main character Ben Hawkins (played by Nick Stahl), a young chain-gang fugitive who is picked up by a traveling carnival following the death of his mother and loss of his home in drought-stricken Milfay, Oklahoma in 1934. The carnival, unsurprisingly, is stocked with colorful and intriguing characters, such as the dwarf man-in-charge Samson and his gimpy crew-boss sidekick Jonesy; the blind mentalist Professor Lodz and the libidinous bearded lady Lila; the snake charmer Ruthie and her strongman son Gabriel; the tarot-reading Sofie, who runs a fortune-telling act with her catatonic (and telekinetic, when angered) mother Apollonia. And then there's the unseen figure referred to as "Management," who has informed Samson that Ben's arrival was not unanticipated.

Cutting between the scenes of the carnival in Oklahoma is the parallel storyline of Brother Justin Crowe, a Methodist minister who (with the assistance of his sister Iris) runs a church in Mintern, California. Brother Justin (played by the magnificent Clancy Brown) is a devout preacher subject to powerful visions, which he takes as signs from God. He also seems to share the same bizarre dreams as Ben (surreal sequences featuring a hulking, tattooed brute, a mysterious figure in tuxedo and top hat, and a Russian soldier on a World War I battlefield), an early indication that the show's parallel plots are destined to converge.

Ben receives his introduction to carny life in this episode, yet feels a strong disconnect from such folk at first. It soon becomes obvious, though, that Ben himself is no ordinary young man--he possesses the Christlike ability to heal others. As the episode concludes, the audience also gets its first clue that Ben's extraordinary power comes at a steep price.

Throughout its two-season run, Carnivale presented an engrossing story filled with ever-deepening mysteries and ever-growing marvels. This initial episode hooks the viewer from the start, making a tacit promise that an incredible ride is in store.

Labels:

A.G.T.V.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Book Review: Sideshow

Sideshow by William Ollie (Dark Regions Press, 2010)

If you write a book in which a mysterious carnival appears on the outskirts of town in October, and in which a pair of young boys square off against a sinister proprietor, then the inevitable comparison will be to Something Wicked This Way Comes. William Ollie (in a post on his blog) has asserted that his book was not written in homage to Ray Bradbury's classic novel, and he even claims that Something Wicked was far from his thoughts when composing Sideshow because he hadn't read it in many years, but I suspect that's just the anxiety of influence talking. Still, there are some prominent differences that should be pointed out: Ollie's novel exhibits a much more adult sensibility, as signaled early on in a prologue scene involving a naked cooch dancer and a lit cigar. Profanity abounds (various characters have a habit of starting sentences with "The fuck..."), and the book features explicit scenes of rape and murder. Diverging from Bradbury's dark fantasy, Ollie has written an out-and-out horror novel.

In contrast to Bradbury, Ollie also spends more time in the novel within his respective carnival, and these scenes represent the strongest part of Sideshow. Hannibal Cobb's Kansas City Carnival is rigged worse than the most dishonest game of chance, masking squalor and danger with the illusion of modern wonder. Deluded fairgoers end up the victims of foul play, and often find themselves transformed into the latest acts in the titular sideshow. There's a motive for all this mayhem, though. Cobb's carnival, which has not arrived accidentally in Pottsboro, South Carolina, is on an unholy mission of retribution.

Sideshow is not a flawless piece of writing. The narrative loses its momentum at times, perhaps due in part to the author's penchant for delving into the characters' inner monologues (as they stop to think questions and ponder the strangeness they've witnessed). Ollie also has a tendency to recount events and repeat details (in this reader's estimation, too much ado is made of the top-hat-shaped black cloud hanging overhead). Nonetheless, the novel offers some vibrant imagery (as reflected by M. Wayne Miller's fabulous cover art) and builds to a blood-soaked climax. Sideshow ultimately does not measure up to its Bradburian precursor (not that it it would be fair to expect it to), but it's a novel that avid fans of the dark-carnival subgenre will no doubt enjoy.

Labels:

Book Reviews

Saturday, August 28, 2010

Movie Review: The Last Exorcism

The Last Exorcism (2010; Directed by Daniel Stamm, Written by Huck Botko and Andrew Gurland)

I have to admit, I went into this film with low expectations. I hadn't read any reviews, but knew Eli Roth's name was attached as a producer, so I was anticipating some Hostel-esque grue applied to yet another Exorcist knockoff. There's no head spinning or projectile vomiting to be spied here, though; no gutter-mouthed girl with nasty masturbation habits. The Last Exorcism is more reminiscent of Paranormal Activity (in its mockumentary form) and Frailty (in its compelling vacillation between psychological and supernatural explanations). And it is an indisputable must-see for horror fans.

Patrick Fabian shines in the role of Cotton Marcus, a Baton Rouge minister who is as much an illusionist as an evangelist. For years he's performed "successful" exorcisms, but he doesn't believe he has actually cast out any demons, merely helped bring peace of mind to those who've convinced themselves that they are possessed. However, when he sees that children nationwide are dying at the well-intentioned but clumsy hands of other exorcists, Marcus resolves to expose the whole ritual as a sham. Like a magician giving away the secrets of his act, Marcus decides to make a documentary that demonstrates his own machinations (to prove his point, he agrees to minister to an allegedly demon-ridden sixteen year old named Nell Sweetzer). Naturally, Marcus gets more than he bargained for, and matters worsen with his every attempt to help Nell. The film forces viewers to consider whether this girl is really possessed, or just deeply disturbed. There's a distinct Southern Gothic vibe to The Last Exorcism (Nell lives with her father and brother on a remote farm in rural Louisiana), with hints of incest suggesting that the horrors transpiring behind the closed doors of the Sweetzer home have nothing to do with Satan's minions. Still, as the film unfolds, the obvious plot twist that the viewer senses coming is that the would-be debunker Marcus will realize that he's encountered the real supernatural deal. But to its credit, the film does not reduce Marcus to some skeptical, Lovecraftian protagonist forced to belatedly acknowledge the occult. The plot proves much more wickedly complex than that.

The Last Exorcism does make a few missteps along the way. After a trying day for Marcus and his two-person crew, his cameraman proposes that they all just stop and take and take a nap--a contrivance that allows Nell to then steal the camera and record her own nocturnal shenanigans. Also, I'm not sure why the second exorcism needed to take place in the family barn, other than the fact that it makes for a creepy setting. And the panic-stricken flight through the woods by one character in the climax seemed too derivatively Blair-Witchy for my taste. Really, though, these are just quibbles. My one main issue is not with the movie itself but with the poster used to promote it. The image employed is both deceptive (no such scene takes place in the movie) and counter-productive to the sense of uncertainty that the film aims to create. As I sat there watching, I kept reasoning that Nell's situation can't be chalked up to fakery or mania if she is going to end up crawling across the ceiling like some human spider. Fortunately, the director Stamm never stoops to such a stunt, which has already been seen in countless other horror movies.

Does the film get too plot-twisty for its own good with its rapid-fire closing sequence? Perhaps. But one thing's for sure: the ending will have you talking as you exit the theater. The Last Exorcism is the type of movie that you need to watch a second time to try to sort out its ambiguities; the ultimate testament of this film's success is that you'll be eager to do just that.

Labels:

Cinemacabre

Friday, August 27, 2010

Make vs. Remake: "The Crazies"

The Macabre Republic feature Make vs. Remake operates according to the same principles as Book vs. Film, offering comparative analysis and a final ranking based on a 10-point-total system (see August 14th's post for full explanation of the scoring system). First up, the non-supernatural twist on a zombie flick:

Make (Directed by George Romero, 1973):

Remake (Directed by Breck Eisner, 2010):

These are two movies made in vastly different eras and on disparate scales. The big budget of the remake enables the film to incorporate plenty of action sequences and special effects, whereas the more modest original is often forced to rely on exposition-laced dialogue to forward its story. Timothy Olyphant (of Deadwood fame) and Radha Mitchell star in the 2010 version, but the 1973 version is populated by virtual unknowns. Such lack of recognizable faces actually reinforces the realism of the original--the sense that the water supply of Anytown, U.S.A. could be tainted by a military-developed toxin that transforms people into homicidal maniacs. Unfortunately, the players employed by Romero are unknown for a reason--their performances are inexpert at best. For instance, Lane Carroll, who plays Judy, is one naturally beautiful woman, but she couldn't out-act a third grader in a school play.

The two films are also set in different parts of the country--Evans City, Pennsylvania (1973 version) and Ogden Marsh, Iowa (2010 version). Romero delves into the woods, while Eisner depicts a more open, rural milieu (but he quickly gothicizes his Iowa, demonstrating that it is no Field of Dreams: the film opens with a high-school baseball game interrupted by a gun-toting crazy who shambles onto the outfield grass).

Romero, unsurprisingly, makes a much stronger political statement in his film. The specter of Vietnam loomed large in 1973, as did a spirit of distrust of the American government. Accordingly, Romero's film is stocked with bureaucratic buffoons and intransigent yet incompetent military men. The remake just doesn't convey the same metaphorical/allegorical significance (even in a world of the H1N1 virus and post-Katrina FEMA infamy).

The eponymous nutcases of the 1973 version lack the quasi-zombie look of their 2010 counterparts; whether this renders them more or less frightful is open to debate. The respective films, though, do an equally admirable job of dramatizing the paranoia of the main characters, who fret about contracting the crazy plague and losing their grip on self-possession.

Eisner's film presents some terrifically horrific scenes, including one involving the best use of a pitchfork in the entire history of cinema. At times, though, the action seems a bit contrived--for example, the car-wash scene, which plays out like a ride through an amusement park funhouse.

Romero, too, arranges some unforgettable moments, such as when a harmless-seeming grandmother figure lashes out crazily with her darning needle. The film also features an utterly disturbing incest scene, as an infected father can no longer inhibit his desires for his daughter.

My major issue with the remake is that I was disappointed by the very end of the movie. Eisner chooses to conclude on a cliched just-when-you-thought-it-was-over note (as the heroes at last reach the presumed safety of a city that has in fact already been contaminated by the toxin). A much more intriguing dilemma could have been addressed: whether the heroes should risk their own freedom/well-being by blowing the whistle on the government's heinous acts (which culminate with the nuking of an American town), or whether they should keep their awful knowledge to themselves so they can attempt to rebuild their lives elsewhere.

Still, this did not detract from my overall enjoyment of what I would deem the best film of American Gothic horror to hit theaters in years. 2010's The Crazies chillingly illustrates the thin line between civilization and chaos, between good neighbor and dangerous adversary. So, sorry Romero purists, I'm going to have to side heavily here with Eisner's updated version:

Make: 2

\

\

\

Remake: 8

How about you? Have you seen either (or both) of these movies? Share your thoughts/reactions in the comments section below.

Labels:

Cinemacabre

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Zombie Potpourri

As the undead continue to thrive in American pop culture, I would just like to alert people to a few zombie-related items...

Recently I learned for the first time (how did I not know about this sooner?!) about the phenomenon of the "zombie walk." It's a wonderfully weird cross between a flash mob and a (decomposing) costume party. Asbury Park, NJ is a popular site for such events; the next walk is scheduled there for October 30 (check out njzombiewalk.com for more info). I've embedded a couple of YouTube videos that captured last year's event.

Now this is what we call a parade in the Macabre Republic:

In this next video, the choreography isn't perfect, but the performances are hysterical:

Terrific stuff; I hope I can attend the upcoming walk on October 30th. And there's more zombie fun to be had the next night, as the Frank Darabont-directed series The Walking Dead will premiere on AMC at 10 (there's a good reason to get home early this Halloween!). Check out the show's trailer here.

Finally, if you can't wait until Halloween weekend to get your zombie fix, there's plenty of good fiction to be had in the meantime. Check out this amazing review (by horror legend John Skipp) of Amelia Beamer's debut novel The Loving Dead.

Recently I learned for the first time (how did I not know about this sooner?!) about the phenomenon of the "zombie walk." It's a wonderfully weird cross between a flash mob and a (decomposing) costume party. Asbury Park, NJ is a popular site for such events; the next walk is scheduled there for October 30 (check out njzombiewalk.com for more info). I've embedded a couple of YouTube videos that captured last year's event.

Now this is what we call a parade in the Macabre Republic:

In this next video, the choreography isn't perfect, but the performances are hysterical:

Terrific stuff; I hope I can attend the upcoming walk on October 30th. And there's more zombie fun to be had the next night, as the Frank Darabont-directed series The Walking Dead will premiere on AMC at 10 (there's a good reason to get home early this Halloween!). Check out the show's trailer here.

Finally, if you can't wait until Halloween weekend to get your zombie fix, there's plenty of good fiction to be had in the meantime. Check out this amazing review (by horror legend John Skipp) of Amelia Beamer's debut novel The Loving Dead.

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Countdown: The Top 20 Stephen King Works of American Gothic Short Fiction--#17

[For earlier entries, click on the "Top Twenty Countdown" label under Features in the sidebar]

#17. "The Last Rung on the Ladder"

King's short story from his first fiction collection, Night Shift, draws on the Gothic convention of the mysterious letter--a message sent to the narrator Larry by his sister Kitty, the contents of which Larry holds back from readers. "The Last Rung on the Ladder" is also a distinctly American piece, as Larry flashes back to the rural Nebraska scene where he and his sister "grew up hicks": "In those days all the roads were dirt except Interstate 80 and Nebraska Route 96, and a trip to town was something you waited three days for." Sometimes Larry and Kitty would entertain themselves in the family's barn, by climbing the ladder leading up to the third loft, shimmying out along the crossbeam, and then stepping off and plunging into the haymow seventy feet below. But these invigorating frolics take an ominous turn when the rickety old ladder splinters as Kitty scales it, leaving her dangling from the last rung. Larry scurries to build an improvised hay mound beneath her just before she slips and falls, and the only physical damage Kitty suffers from the mishap is a broken ankle.

Tragedy, though, has not been averted, merely postponed. Flashing forward again to the present, Larry reveals the reason he and his father have just returned from California: they were there to attend Kitty's funeral. Nine days earlier, Kitty committed suicide by jumping from the top of an insurance building in Los Angeles.

Larry's narrative ultimately addresses not "the incident in the barn" but the more profound fall from innocence. He now carries in his wallet a terrible news clipping about Kitty, "the way you carry something heavy, because carrying it is your work. The headline reads: CALL GIRL SWAN DIVES TO HER DEATH." Larry bears a huge burden of guilt, because if he hadn't fallen out of touch with his sister, she might not have ended up jumping from the insurance building. He concludes by finally sharing the contents of the letter he received from Kitty: an obvious cry for help in which she states she would have been better off if she'd died that day in the barn. The letter is postmarked two weeks prior to her suicide, but Larry didn't receive it in time, because he never provided Kitty with his current address as they drifted apart over the years. Larry's realization of his own negligence, his failure to help save Kitty from her fatal descent through adult life, makes for a devastating denouement.

"The Last Rung on the Ladder" is a human story, a heartbreaking story. It serves as an early indication that Stephen King has more to offer than just monsters and carnage; he is also a master of quiet horror.

One final note: Fans of King's early short fiction will be sure to love the audiobook The Stephen King Collection: Stories from Night Shift. Actor John Glover does an incredible job of reading/performing King's lines. Personally, I love to pull the Night Shift: to grab the book off the shelf late at night, pop in the corresponding CD, and read along as I lie in bed in listening. It's a doubly-pleasurable experience, one I recommend not just to King's Constant Readers but also to writers looking to prime their imaginations for dreamtime.

Labels:

Top 20 Countdowns

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Grue Bayou: "Swamp People"

Louisiana's swamplands have provided the setting for many works of American Gothic over the years, from fiction (Lucius Shepard's Green Eyes; Robert R. McCammon's Gone South) to film (The Alligator People; Interview with the Vampire) and television (True Blood). And now the new reality series airing on The History Channel, "Swamp People" can be aligned with that tradition.

The show traces the lives of the mostly-Cajun residents of southern Louisiana (the vast region of flooded forests, marshes, and bayous comprising the Atchafalaya River Basin). As the show's narrator establishes, "This is a hidden world where nature rules...and man fights [or was it "bites"?] back." The most rugged of these men engage--during the legalized 30-day hunting season--in alligator hunting. Their efforts are not mere sport, but a matter of earning a living and also protecting their loved ones (left unchecked, the alligator population would pose a serious threat to human inhabitants of the area).

Thematically, the show's first episode focuses on hunter Troy Landry's years-long quest to track down his personal "white whale": the behemoth gator known as Big Head. The Jaws overtones are also strong here, as Troy struggles to keep summer fun from turning into a bloody disaster. He aims to kill Big Head before the gator "eats one of them kids" swimming innocently (some might say crazily--such aquatic activity looks about as safe as trying to blow-dry your hair in the shower) in the murky waters. The show's rhetoric of monstrosity, though, hardly seems overblown when one sees the rotted chickens employed as bait or hears the beastly growl of an agitated gator.

As one might guess from its title, the series features a colorful cast of real-life characters. None of these people will be starring in a Crest commercial anytime soon, but it's important to point out that unlike many a reality-TV show, "Swamp People" is not some shameless parade of freakishness. These are proud and skilled folk, adept at living off the (swamp)land and killing off the saurian predators haunting their world (emphasis on "haunting": video clips on the show's webpage indicate that future episodes will touch on the dark folklore of the area).

While I am an avowed despiser of the reality-television genre, I love what I've seen thus far of "Swamp People." The show offers a fascinating glimpse of a way of life that lies far from the American mainstream but cuts straight through the Macabre Republic.

Note: If you missed the series premiere on Sunday night, you can catch a repeat of that first episode tonight at 10 on The History Channel.

Labels:

A.G.T.V.

Monday, August 23, 2010

Comments Lottery

Hi everyone. This is another double-post day, as I'd just like to take a moment to announce an upcoming prize drawing here at Macabre Republic. In an effort to draw lurkers out of the Web-work (no shame there--I've been known to lurk myself; took me years to officially join the Shocklines message boards), I'm going to be running a "comments lottery." The idea is very simple: for each and every comment you leave on any of this month's posts, you'll be entered into a drawing for a $25 (the magic number to qualify for free shipping) gift card from Amazon.com. A single comment enters you into the lottery, but the more comments you leave, the better the odds that you'll be the person who has his/her name drawn (by the way, it's important that you identify yourself by name when commenting--I won't be able to distinguish your contribution if you just enter under "Anonymous"). The only other caveat is that we're talking actual comments, not spam; there is no minimum length requirement, as long as the comment is legitimate (I reserve the right to discount any comments that do not adhere to the spirit of the contest--e.g. don't just start up a running dialogue with a friend in the comments section of a post).

The lottery's open period starts now and runs up until midnight on August 31st. The winner will be announced here on September 1st.

So commence commenting, and good luck!

The lottery's open period starts now and runs up until midnight on August 31st. The winner will be announced here on September 1st.

So commence commenting, and good luck!

Labels:

Contests

Short Story Spotlight: "Silverman's Game"

Here at Macabre Republic, I aim to review not just full-length books but also individual short stories. In particular, I hope to call attention to some quality works of short fiction published in the small press, pieces that might have been overlooked thus far but are deserving of a wider audience. Today's spotlight story: "Silverman's Game" by Matt Moore (Damnation Books, June 2010).

In terms of structure and setting, Moore's story has all the trappings of a traditional spook tale: an adult narrator who flashes back to a traumatic incident from his childhood, when he, his older brother, and his brother's friend foolishly broke into a creepy old house. "Silverman's Game," though, quickly comes into its own when the titular villain Silverman catches the young trio in the act, locks them in his basement, and forces them to participate in a fiendish game. The boys face a crisis of survival worthy of the original Saw movie (i.e. a simple but harrowing premise, not the ridiculously elaborate traps of the gory sequels). I don't want to reveal too much here for fear of spoiling the reader's pleasure of encountering the plot firsthand, but I'll just say that the predicament involves a gun loaded with a single bullet.

Moore writes clean, unaffected prose, and does a fine job here of capturing the voice/viewpoint of a twelve-year-old boy. The suspense of the narrative builds steadily throughout (as the boys struggle to find some way to break Silverman's terrible rules), and the climax delivers a surprising twist. Overall, this is a quick, entertaining story, one that reads like the textual equivalent of a Tales from the Darkside episode. "Silverman's Game" is well worth playing, as the reader gets plenty of bang for the (little more than a) buck it costs to purchase this ebook from Damnation Books.

Labels:

Short Story Spotlight

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Poll: Vote For Your Favorite American Haunted-House Novel

Now that the conclusion of the critical essay on The Haunting of Hill House has been posted, I figured it would be a good time to conduct a poll asking readers to vote for their favorite American haunted-house novel.

"American" here designates the setting of the novel, not the national origin of the author. Henry James's The Turn of the Screw is a classic haunted-house novel written by an American, yet does not qualify as American Gothic thanks to its English countryside setting. Conversely, the Britain-born Clive Barker makes the list by writing about a haunted Hollywood mansion.

I toyed with the idea of including Jay Anson's allegedly nonfictional The Amityville Horror as a choice, but ultimately decided against it.

The list of choices appears in the poll over in the right sidebar, but just for the record, they are:

*Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story by Clive Barker

*House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

*The House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne

*The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

*The Shining by Stephen King

*Audrey's Door by Sarah Langan

*Burnt Offerings by Robert Marasco

*Hell House by Richard Matheson

*Beloved by Toni Morrison

*The House Next Door by Anne Rivers Siddons

*Other

So go ahead and give a quick click in the sidebar for your personal favorite. If you'd like to speak more about your choice (or identify the book if you voted for "Other"), you can leave a comment to this post.

The poll will close at 11:59 P.M. on Saturday, August 28th.

"American" here designates the setting of the novel, not the national origin of the author. Henry James's The Turn of the Screw is a classic haunted-house novel written by an American, yet does not qualify as American Gothic thanks to its English countryside setting. Conversely, the Britain-born Clive Barker makes the list by writing about a haunted Hollywood mansion.

I toyed with the idea of including Jay Anson's allegedly nonfictional The Amityville Horror as a choice, but ultimately decided against it.

The list of choices appears in the poll over in the right sidebar, but just for the record, they are:

*Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story by Clive Barker

*House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

*The House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne

*The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

*The Shining by Stephen King

*Audrey's Door by Sarah Langan

*Burnt Offerings by Robert Marasco

*Hell House by Richard Matheson

*Beloved by Toni Morrison

*The House Next Door by Anne Rivers Siddons

*Other

So go ahead and give a quick click in the sidebar for your personal favorite. If you'd like to speak more about your choice (or identify the book if you voted for "Other"), you can leave a comment to this post.

The poll will close at 11:59 P.M. on Saturday, August 28th.

Labels:

Polls

Haunting Anniversary: A Half-Century of Hill House (Part Three)

[The final installment of the essay that began on Friday.]

III.MODEL HOMES

The 50th Anniversary of the publication of The Haunting of Hill House marks an appropriate time not only to look back on the novel itself but also to note its subsequent influence. To date there have been two film versions: Robert Wise's faithfully atmospheric The Haunting (1962), and Jan de Bont's abominable, CGI-rife remake (1999), the latter as critically panned as the former is acclaimed. Still, the book's greater legacy can be traced in the realm of fiction. Over the past five decades, Hill House has provided an architectural blueprint for a slew of haunted houses in the horror community. Consider the following macabre McMansions that have sprung up across the American Gothic landscape:

Richard Matheson's Hell House (1971) stands as a more graphically violent and sexually charged version of Hill House. The basic plot parallels here are hard to miss: an investigating foursome move into a remote New England house of horrors (in which the servant couple from a neighboring town refuse to sleep [Matheson 3]). Moreover, the character of Florence Tanner clearly mirrors Eleanor Vance. At first sight Florence exclaims that Hell House is "hideous" (27), echoing Eleanor's initial outraged reaction to Hill House. Eleanor balks at entering the library because of the perceived stench; Florence can't go into the chapel because the "atmosphere here is more than [she] can bear" (35). Much like the psychologically fragile Eleanor, Florence represents the group's "weakest link" (286), and dies after being fiendishly duped by the ghost haunting Hell House.

Anne Rivers Siddons's Southern gothic novel The House Next Door (1978) involves a recently-built but malignant home ("haunted" by the latent evil of its architect) that preys "on the weakness and inherent flaws in the characters of the people who live there" (Siddons 327). Siddons has cited Hill House "as nearly perfect a haunted-house tale as I have ever read" (qtd. in King, Danse Macabre 259), and such reading has left a discernible imprint. Planning to set fire to the neighboring home, Siddons's narrator Colquitt Kennedy comments in the book's prologue that "[i]n another time they would have plowed the charred ground and sowed it with salt" (5)--a remark echoing Dr. Montague's indirect quote of a former tenant of Hill House, who "ended by saying that in his opinion, the house ought to be burned down and the ground sowed with salt" (Jackson 51).

The titular domicile of Peter Straub's 1980 novel Shadowland (a "haunted house" [170] in the sense that it brims with the dark magic of the master conjurer residing there) exists several miles beyond a town whose very name recalls the village of Hillsdale in Jackson's novel: "Hilly Vale" (162). During a summer apprenticeship at Shadowland back when he was 15, protagonist Tom Flanagan "felt the house claiming him" (320), and "[i]t seemed to him that he could visualize every inch of the house, every curve of the stair posts, every watermark in the kitchen sink" (319)--sensations similar to Eleanor's ostensible communion with Hill House toward the end of Jackson's novel. The tunnel below Shadowland formerly used for "bootlegging" (375) also serves as a literalization of Eleanor's early fancy of "a passageway going off into the hills and probably used by smugglers" (Jackson 23).

Marvin Kaye and Parke Godwin's A Cold Blue Light (1983) builds upon the same foundation that Matheson did earlier: a team of scientists and mediums descends upon the Pennsylvanian manse known as Aubrey House. Another Eleanor Vance clone appears in the person of Vita Henry, a sexually-frustrated woman tragically seduced into believing that Aubrey House "welcomed and protected her" (144). The cold blue light seemingly rooted in the upstairs hallway of Aubrey House also brings to mind the cold spot fixed outside the door of Hill House's second-floor nursery.

In his short novel Elsewhere, Exorcist scribe William Peter Blatty has a quartet of investigators--a group led by a university professor with research interests in the paranormal--settle into a labyrinthine mansion ("it's disordered, no sense to where anything leads" [613]) with a shady reputation. Blatty (whose plot ultimately offers a clever twist on the haunted house formula) echoes famous fright moments from Jackson's novel and Wise's film, most notably the scene of a furious, inexplicable pounding on a bedroom door.

In his postmodern horror novel Demon Theory (2006), Stephen Graham Jones diligently cites his sources within a slew of endnotes. Note 29 (occasioned by the characters' first glimpse of the ominous house in the novel) appropriately reads: "In Shirley Jackson's 1959 urtext The Haunting of Hill House, Eleanor's first thought after turning 'her car onto the last stretch of straight drive' and encountering Hill House 'face to face' is that the house is vile. Her second thought is 'get away from here at once'" (Jones 380).

Sarah Langan's Audrey's Door (2009) wears its influences on its leaves (in a short preface, the author lists The Haunting of Hill House first among the texts that "particularly inspired" her novel). The book's haunted Manhattan apartment building proves just as architecturally askew as Hill House: "The Breviary's floors differed in height from one story to the next, and its walls didn't intersect at right angles but were either obtuse or acute" (9). Recent renter Audrey Lucas--a socially awkward, emotionally unstable thirtysomething who's been scarred by her lifelong struggle with her mentally ill mother--also reflects Jackson's protagonist when she sees "through the Breviary's eyes" (388) and achieves an omniscient awareness of events throughout the building. Perhaps Langan's most impressive echo of Jackson, though, comes in the opening of Chapter 41 "The Breviary" ("No thinking creature can tolerate captivity. In the presence of just four white walls, the mind invents [...]" [371])--a clever pastiche of Hill House's famous "No live organism..." first paragraph.

Labels:

Dark Articles

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Haunting Anniversary: A Half-Century of Hill House (Part Two)

[The second installment of the essay that began with yesterday's post.]

II.WALKING THE HOUSE

A strictly psychological reading of the events of the novel does not suffice; Eleanor's troubled subconscious is not the true source of the haunting at Hill House. Yes, Eleanor appears capable of telekinesis (an ability she consciously denies), as suggested by the repressed "showers of stones" incident (3) when Eleanor was twelve and still distraught over her father's death a month earlier. And yes, she carries a lot more baggage to Hill House than her one suitcase. She's spent the past eleven years (from age 21-32) nursing her invalid mother, a miserable period marked by "small guilts and small reproaches, constant weariness and unending despair" (3). Her life circumstances have no doubt stunted her personal growth: Eleanor "had spent so long alone, with no one to love, that it was difficult for her to talk, even casually, to another person without self-consciousness and an awkward inability to find words." It is certainly tempting to read this backstory into Eleanor's experiences at Hill House. For instance, her underlying guilt that she is to blame for her mother's death--because she didn't awake and respond to her mother's knock on the bedroom wall--can be seen to manifest as the awful pounding on the bedroom door at Hill House. Similarly, the "cold air of mold and earth" (75) that (only) Eleanor senses within the library might merely be an association on her part of the library's books with those she had to read aloud to her mother "for two hours every afternoon" (62). The cold spot inside the doorway to the nursery likewise can be linked to Eleanor's shame at having to sleep (as she finally admits to the others at novel's end) "in the baby's room" (177) of her sister's home.

By the same token, the hatred Eleanor feels for her family can be seen to color her relationship with her pseudo-sibling Theodora. Did Eleanor (who in her self-consciousness is quick to sense persecution by others) bloody Theodora's more stylish wardrobe in retaliation, resenting Theodora's suggestion that Eleanor herself had scribbled the message "HELP ELEANOR COME HOME" (107) on the wall of the upstairs hallway? Before chalking up the incident to a fit of telekinetic rage, though, one must note that the initial hallway message was written in chalk. At the start of the scene immediately following the soaking of Theodora's clothes, Luke Sanderson reads from a book he's removed from the Hill House library: "It was the custom, rigidly adhered to [...] for the public executioner, before a quartering, to outline his knife strokes in chalk upon the belly of his victim--for fear of a slip, you understand" (116). The timing and nature of the detail raises the idea that whatever haunts Hill House has acted to "quarter" the four human investigators by turning them against one another. One simply cannot discount the possibility that the haunting agent taps into Eleanor's fear and loathing (much like the telepathic Theodora repeatedly reads Eleanor's mind) and uses this insider information to insidious advantage. The strange happenings at the house (e.g. thunderous pounding on the bedroom door while Montague and Luke are simultaneously lured away by a canine apparition) seem too complex and diverse to be the mere product of telekinesis, however prodigious Eleanor's talent might be.

Labels:

Dark Articles

Friday, August 20, 2010

Haunting Anniversary: A Half-Century of Hill House (Part One)

October 2009 marked the 50th Anniversary of Shirley Jackson's masterwork, The Haunting of Hill House; in honor of that occasion, I wrote a critical essay that was ultimately published in the February 2010 issue of The Internet Review of Science Fiction. Over the course of the next three days, I will post that same essay here on Macabre Republic. In today's first installment, I consider the critical commentary that has accrued over the past half-century, pointing out how such analysis has actually led readers astray. In Part Two tomorrow, I will offer my own close reading of the novel, culminating with the identification of the specific ghost haunting Hill House. And on Sunday, I will survey the various haunted-house novels influenced by Jackson's book, and offer my final appraisal.

The essay is written in MLA format, giving parenthetical citations of quoted sources. A Works Cited section providing complete bibliographical information will appear at the end of the essay on Sunday.

Hope the essay inspires you to re-read Jackson's classic novel (if you've never ventured inside Hill House before, stop right now and go pick up a copy for yourself--it's time to find out what you've been missing all these years!).

Haunting Anniversary: A Half-Century of Hill House

By Joe Nazare

In the oft-cited opening paragraph of The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson writes: "Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it has stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more" (1). The enigmatic novel itself (first published by The Viking Press in October 1959) has now stood for fifty years, holding darkness within seemingly for the duration of its existence. This golden anniversary thus marks an appropriate time to shine new light on the book, to reinvestigate Hill House and to consider the half-century legacy of Jackson's monumental work of dark fantasy.

I.LANDSCAPING

Regrettably, the ivy of literary criticism attached to Hill House has tended to obscure its finer features. Biographers, scholars, and pop-culture commentators alike have proven dubious guides, telling tales riddled with factual error and taking interpretive leaps that a careful reader hesitates to follow. The first step, then, to pushing toward a clearer understanding and interpretation of the novel involves hacking through such accrued verbiage.

Labels:

Dark Articles

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Countdown: The Top 20 Stephen King Works of American Gothic Short Fiction--#18

#18. "Dolan's Cadillac"

In this dark-crime novella collected in Nightmares & Dreamscapes, King modernizes and Americanizes Edgar Allan Poe's classic revenge tale, "The Cask of Amontillado" (which is set in an unnamed European city during Carnival season). Would-be government witness Elizabeth Robinson is killed by a car bomb before she can ever testify against the titular gangster Dolan. And so for the next nine years her husband watches and waits (all the while goaded by the ghostly voice of his dead wife inside his head) for the opportunity to dish out appropriate retribution. Finally, Robinson hatches a plan to dig "the world's longest grave" on a dark desert highway (cue the Eagles music) stretching between Los Angeles and Las Vegas; he will bury Dolan alive inside the very Sedan DeVille he is chauffeured around in, converting the vehicle into "an upholstered eight-cylinder fuel-injected coffin."

King's narrative skills are perfectly employed in this self-described "archetypal horror story, with its mad narrator and its account of a premature burial in the desert." The author ratchets up the suspense as only he can, detailing Robinson's rigors and fears as the still-grieving widower sets up his elaborate trap. The climactic confrontation between Robinson and the trapped Dolan is also a virtuoso act of scene-building on King's part. Here the echoes of Poe's Montresor and Fortunato characters grow quite strong, as Robinson answers his victim's screams with those of his own, and mocks Dolan's desperate cries:

"For the love of God!" he shrieked. "For the love of God, Robinson!"

"Yes," I said, grinning. "For the love of God."

I put the chunk of asphalt in neatly next to its neighbor, and although I listened, I heard him no more.Still, this isn't the end of the story, because Robinson (even as he succeeds in his murderous scheme) becomes haunted by the bogeyman image/mad laughter of Dolan. King proves to be an astute student of Poe, picking up on a key (yet often overlooked) fact of Montresor's narration: for all its superficial bravado, Montresor's tale--told fifty years post facto--has an undercurrent of guilt and dread running through it.* As Robinson's sanity caves inward, the reader of King's novella is forced to consider that much like the patch of faux roadway that dooms Dolan, vengeance might not be all it's cracked up to be.

* If you'll forgive a bit of shameless (is there really any other kind?) self-promotion: this is the same undercurrent that I trace out in my short-story sequel to "A Cask of Amontillado," entitled "Something There Is" (available as a free podcast [episode #166] from Pseudopod).

Labels:

Top 20 Countdowns

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Take a Dip in the M.R. Trivia Pool

Today's game is like a combination of a crossword and a word jumble. I present four trivia questions related to American Gothic, and provide the number of letters in each answer. All the letters comprising the answers are drawn from the letter pool preceding the questions, so you can cross the letters off as you go (each successful answer will thus improve your chances of coming up with the correct responses to the other questions). The letters that have an asterisk (*) underneath them can then be unscrambled to form the answer to the (separate) bonus question.

So grab your pencil and scratch paper, and good luck. If you think you've got the answers, go ahead and post them as a comment. If no brave souls step forward, I will supply the answers tomorrow in the comments section of this post.

First, the letter pool:

M D R S N E M L S

L P I O S Y E S O

O R H G U E A E M

E O Y Y A R T S O

And now the trivia questions:

1.The one word The Stand's Tom Cullen would get right in a spelling bee:

_ _ _ _

*

2."The foulest stench is in the air / The funk of forty thousand years / And grisly ghouls from every tomb are closing in to...

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* * *

3.Dick Hancock's partner in crime:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* *

4.End of the world for Twilight Zone bibliophile Henry Bemis when he breaks his...

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* * * *

BONUS. New York cigar store girl who inspired a Poe story:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

So grab your pencil and scratch paper, and good luck. If you think you've got the answers, go ahead and post them as a comment. If no brave souls step forward, I will supply the answers tomorrow in the comments section of this post.

First, the letter pool:

M D R S N E M L S

L P I O S Y E S O

O R H G U E A E M

E O Y Y A R T S O

And now the trivia questions:

1.The one word The Stand's Tom Cullen would get right in a spelling bee:

_ _ _ _

*

2."The foulest stench is in the air / The funk of forty thousand years / And grisly ghouls from every tomb are closing in to...

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* * *

3.Dick Hancock's partner in crime:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* *

4.End of the world for Twilight Zone bibliophile Henry Bemis when he breaks his...

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* * * *

BONUS. New York cigar store girl who inspired a Poe story:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Labels:

Games/Trivia

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Book Review: A Book of Tongues

A Book of Tongues by Gemma Files (Chizine Publications, 2010)

This first novel from long-renowned short-fiction writer Gemma Files reads like Deadwood by way of Tim Powers, William Burroughs, and Clive Barker. Like Powers's pirate novel On Stranger Tides, A Book of Tongues melds fantasy and history (Files includes the real-life figure of Allan Pinkerton as one of the characters in her tale of magic-wielding outlaws in the post-Civil-War American West). Like Burroughs's The Place of Dead Roads (a phrase that Files employs in her novel), this genre-bending work features homosexual gunslingers in its cast. And like Barker's The Hellbound Heart, the book involves a love quadrangle, numerous betrayals, and a trip to the underworld that leaves one man skinless.

But all this is not to suggest that A Book of Tongues is simply derivative. Files exhibits incredible originality, particularly in the system of magic-making that she maps out. Mages aren't built for peaceful coexistence, given their vampiric hunger for each other's power--a situation that creates some spectacular conflict between characters. Also, one of the ways a person's latent talent for "hexation" can express itself is as a result of suffering a grievous bodily harm. The Confederate soldier/preacher Asher Rook undergoes such growing pains when he survives a hangman's rope and transforms into a formidable hexslinger. His pocket Bible is now his "Bad Book," whose words he literally spreads, to deadly effect: when he blows on the opened tome, "the text lift[s] from those gilt-edged pages in one flat curl of unstrung ink, a floating necklace of black Gothic type borne upwards on a smoky rush of sulphur-tongued breath."

Labels:

Book Reviews

Monday, August 16, 2010

Get 'Em While They're Young!

This weekend I was browsing in the local B&N, and just happened to stop and take a look at the books stacked atop the Summer Reading tables. I was surprised by some of the selections, to say the least (Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters?!), yet also delighted in discovering that so many of the books assigned to students this summer qualify as American Gothic.

--There were books about serial killers both fictional:

(The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold)

--And nonfictional:

(The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson)

--A dark and twisted family saga:

(If There Be Thorns/Seeds of Yesterday by V.C. Andrews)

--A classic of Southern Gothic literature:

(To Kill a Mockingbird: 50th Anniversary Edition by Harper Lee)

--And Southern Gothic plus bloodsuckers:

(Interview with the Vampire by Anne Rice)

--A novel of Boarding-School Gothic:

(A Separate Peace by John Knowles)

--A novel of racially-charged crime and punishment (that also riffs on Poe's "The Black Cat"):

(Native Son by Richard Wright)

--Even a book featuring a real-life descent into a labyrinthine underworld:

(The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City by Jennifer Toth)

All in all, quite a macabre curriculum.

Those lucky kids.

Venture back tomorrow, when I'll be reviewing a book that I can confidently say will never be deemed suitable material for a high school English class.

--There were books about serial killers both fictional:

(The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold)

--And nonfictional:

(The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson)

--A dark and twisted family saga:

(If There Be Thorns/Seeds of Yesterday by V.C. Andrews)

--A classic of Southern Gothic literature:

(To Kill a Mockingbird: 50th Anniversary Edition by Harper Lee)

--And Southern Gothic plus bloodsuckers:

(Interview with the Vampire by Anne Rice)

--A novel of Boarding-School Gothic:

(A Separate Peace by John Knowles)

--A novel of racially-charged crime and punishment (that also riffs on Poe's "The Black Cat"):

(Native Son by Richard Wright)

--Even a book featuring a real-life descent into a labyrinthine underworld:

(The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City by Jennifer Toth)

All in all, quite a macabre curriculum.

Those lucky kids.

Venture back tomorrow, when I'll be reviewing a book that I can confidently say will never be deemed suitable material for a high school English class.

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Countdown: The Top 20 Stephen King Works of American Gothic Short Fiction--#19

Next up on the Countdown (if you've missed a previous entry, just click on the "Top Twenty Countdowns" label in the right sidebar):

#19. "Rest Stop"

While driving home late at night from a Florida mystery writers group meeting, John Dykstra ponders his double life as a "literary werewolf" (by day he is an urbane professor of English at FSU, but he moonlights as an author--under the pseudonym "Rick Hardin"--of a series of crime novels featuring the "urban warrior" hitman-character, the "Dog"). This duality comes into play when a pressing need to relieve himself leads Dykstra to pull off at a highway rest stop. At first he is paralyzed when he overhears a man brutally beating his pregnant girlfriend inside the women's room, but then Dykstra finds the courage to intervene by turning to his Hardin alter ego.

The only problem is, "Hardin" proves more vigilante than knight in shining armor, using excessive force to subdue the abusive male, Lee. Hardin is surprised by his own actions after giving the prostrate figure a sharp kick in the hip, but what dismays him even more is "that he wanted to do it again, and harder. He liked that cry of pain and fear, could do with hearing it again." And then he can't help but wonder "how hard he could kick old Lee-Lee in the left ear without sacrificing accuracy for force." When first approaching the rest stop, Dykstra's writerly imagination pictures a lone missile command silo somewhere in the American heartland, "and the guy in charge is suffering from some sort of carefully-concealed (but progressive) mental illness." The final turn of the screw in King's story, though, is that such burgeoning craziness might be an apt description of Dykstra/Hardin himself.

King has gone the "unruly pseudonym" route before (cf. The Dark Half), but never as succinctly as he does here in "Rest Stop" (incidentally, in the notes at the end of Just After Sunset, King explains that the story was drawn from a similar experience inside a Florida rest stop, a situation that forced him to think, "I'll have to summon my inner Richard Bachman here, because he's tougher than me."). The story points to the savagery always lurking just beneath the surface of human civility; Dykstra realizes that "under the right circumstances, anyone could end up anywhere, doing anything." Besides drawing on the Jekyll-and-Hyde archetype, the story utilizes the time-honored motif of the "wrong turn" (while facing the predicament of how to deal with the ruckus inside the women's room, Dykstra deems his stopping off at that particular rest area "the evening's great mistake"). But perhaps what truly distinguishes this work of American Gothic is King's depiction of the rest-stop setting. Even at the best of times, these way stations have a forlorn air about them; after all, they are designed to facilitate transience (an appropriate ad banner might be "Eat. Excrete. Retreat."). And when encountered in their desolate, late-night state, they can be downright ominous. King seems well aware of this as he transforms a rest stop on the open road between Jacksonville and Sarasota into a Gothic locale, complete with missing children posters papering the walls and alligators presumably lying in the building's swampy perimeter.

So next time you're out riding the highway in the wee hours of the morning and you feel nature calling you as you come up on a rest stop, just remember: good things come to those who wait until they get home.

Labels:

Top 20 Countdowns

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Book vs. Film: The Killer Inside Me

"Oh, the book's always better than the movie."

Well, the recurring feature Book vs. Film aims to put that maxim to the test. I'll compare the novelistic and cinematic versions of a narrative, noting what each does better than the other, and concluding by offering a comparative ranking. (A word of warning: unlike standard book and movie reviews, this feature presumes the audience is already familiar with the subject being discussed. Plot spoilers could be included in the commentary.)

The ranking will be done on a 10-points-total system. Imagine that there are ten gold coins to be placed on the opposing arms of a scale. If both the book and film were considered to be on the same level quality-wise, then the coins would be distributed evenly and the final result would be 5-5. If the book was deemed slightly better than the movie, the scoring might be something like 6-4 (tilting the imaginary scales to the left); if the film version totally outshined the novel, then a 2-8 or even a 1-9 slant could result.

Labels:

Cinemacabre

Friday, August 13, 2010

Interview: Rich Ristow

Rich Ristow is a Rhysling Award-winning poet whose books include Into the Cruel Sea (Skullvines Press), Binge and Purge (Skullvines) and Wood Life: A Poem (Snuff Books). He's edited the soon-to-be-released Death in Common: Poems from Unlikely Victims, and has plans for many other anthologies (Rich is the Managing Editor of the Needfire Poetry imprint of Belfire Press). In 2004, he earned a Master of Fine Arts in poetry from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

This past week Rich graciously agreed to do an interview with Macabre Republic. We discussed his own writerly and editorial projects, as well as his thoughts on the present state of the art of "horror" poetry.

Macabre Republic: Hello, Rich, and welcome to Macabre Republic. I'd like to start by talking about your book-length poem, Wood Life. I was really impressed by the range of the verse, in terms of the poetic modes adopted and structural patterns employed. From section to section of the poem, the verse seemed as varied as the mental/emotional states of your tormented speaker. How conscious were you of matching form to content in Wood Life? Also, in terms of the composition process: did you find there are any special challenges in writing a book-length poem?

Rich Ristow: Charles Olson and Robert Creeley both believed that content is but an extension of form, and I have to agree 100%. Basically, what you say and write is shaped by how you say or write it. This is why, for example, a sonnet in iambic pentameter sounds absolutely different than the drunken free verse of Charles Bukowski; one sounds lofty and elevated, and the other like the guy sitting one bar stool over--and I'm not saying that one is better than the other. Poetic forms are basically tools to achieve a desired end. For example, one wouldn't use a scalpel to do the job of a hacksaw; so, one wouldn't write a villanelle to achieve the minimalist juxtaposition of haiku, senryu, and tanka.

That's a wordy preamble to my answer, filled with name dropping, I know. However, it's what was going through my mind when writing Wood Life. Psychology is messy at times, and I wanted the form to be as fragmented and unpredictable as the speaker's psychosis and moral crisis. So some days, he thinks linear, which translates into ordinary lines, and other days, the writing scatters across the page in a jumbled mess with gaps and blank spots. This is also why the book looks so rough with orphaned lines carrying over to blank pages, a few typos, and incorrect capitalization. The challenge, however, is to not only capture this sort of chaotic mind onto paper, but to also make it readable to a general reader. A lot of postmodernist poetry, while wonderful and challenging, will not appeal to the average genre fiction fan. It will appeal to people like myself, who have spent many years studying poetry, and that's about it. So it was something I spent a lot of time thinking about, and in organizing the book, I tried to keep most of the sections slightly different than what came before.

Labels:

Interviews

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)